Rick Hall on calling up Jerry Wexler, recording Aretha, and being besties with the Wicked Pickett

Tonight at 10 PM EST / PST, the ongoing PBS documentary series Independent Lens offers the network premiere of Muscle Shoals, which shines a spotlight on the Alabama city where thousands of classic songs have been recorded over the years, many of them at FAME Studios, founded by Rick Hall. We had an opportunity to chat with Hall, who discussed the founding of his studio, hit on some of his career highlights, and talked about working with Aretha Franklin, Wilson Pickett, and even the Osmonds.

Rhino: How did you find your way into having a studio in Muscle Shoals in the first place?

Rich Hall: Well, I quit my job at Reynolds Metal making tin foil, built (FAME Studios), set it up, and said, “Let’s do it!” [Laughs.] That’s what happened.

Was that something you’d always had an eye on doing, or was it just on a whim?

No, I had played music all my life. I’d been playing since I was six years old, me and my sister sang in gospel quartets, and all that kind of crap, so I had a lot of experience. I was in the high school band, and we won first place in the state of Alabama for a string-band contest, so I’d been on radio stations and worked gigs for many years. So I was familiar with what I wanted to do. And I was a songwriter and a singer – I had my own band called the Fairlanes – but when the crunch time came in the 1960s, I quit making country music because I was writing country songs and having a lot of success with ‘em. I had hits with George Jones, Brenda Lee, Roy Orbison, and people like that, so I’d made a little money at it, and I just decided to do it full-time.

How was it for you to shift to a behind-the-scenes role after having been out front? Was it an easy transition for you?

No, not at all. But that’s what I wanted to do: I wanted to be a record producer, and I wanted to be a songwriter. I didn’t really want to be an artist. I wanted to be an executive, and I wanted to own a record label…and I eventually did! I was in my element, and I was having fun.

Did you set out to focus on R&B, or was it just luck of the draw as far as who came to the studio?

No, it wasn’t luck of the draw. I went into R&B music and started producing black acts because I couldn’t get a gig anywhere else! I went to Nashville and tried to go country and do all that stuff, and nobody wanted me. So I set up shop in Muscle Shoals, built the studio, and decided to go into working with black acts...and the first two black acts I produced, I had hit records with ‘em. Big hit records. One was “You Better Move On,” by Arthur Alexander, which later was covered by the Rolling Stones, the Hollies, and so forth, and the second one was by Jimmy Hughes, a record called “Steal Away.” And then I was working with the Tams when they having a lot of big hit records, producing “What Kind of Fool (Do You Think I Am),” which was a big hit for them. Bill Lowery brought that group out of Atlanta, Georgia. You know, I’ve been in the music business all my life. Well, not yet, I hope. [Laughs.] But I’ve done everything you can possibly do, and I’ve produced every act you can possibly think of. The acts I haven’t produced just haven’t been worth producing.

The documentary talks about how Percy Sledge’s “When a Man Loves a Woman” was a major turning point for the studio, even though it wasn’t actually recorded there.

No, that wasn’t cut in my studio. It was cut by Quinn Ivy, who was a songwriter for me, and Marlon Greene. They were the two producers of that record, and they were both signed to my company, I think, at one time or another as songwriters, which was FAME Publishing Company, so they asked me…well, Quinn asked me, “Look, I’m writing for you, but do you mind if I pick up the leftovers of your stuff that you turn down?” And I said, “No, I don’t mind at all.” So he said, “Well, I’m getting a console from the radio station where I’m working, and I’m gonna build a studio, but it won’t be anything like yours, so…can you send me some acts?” So I said, “Sure, go ahead and do it. Whatever. I can’t do it all!” [Laughs.] And they produced “When a Man Loves a Woman,” with Percy Sledge.

Now, I did have something to do with it, though, because they brought it to me when they had it finished, and said, “Do you know of a place where we can get a record deal on Percy?” And I said, “Yes, I do. I’ll call Jerry Wexler.” So I called Jerry Wexler and said, “I’ve got a hit record that these guys want to get rid of, and you told me that if I found something I liked, send it to you and you’d work with me on it, so I’m sending it to you.” He said, “Well, send it up to me, Rick, and I’ll get back to you.” And he got back to me and said, “I don’t think it’s a hit.” And I said, “Well, you’ve lost your hearing.” [Laughs.] He said, “What do you mean?” And I said, “It’s a number-one record! Number one worldwide! All over the world!” He said, “That’s awful strong, Rick,” and I said, “It is strong. But that’s how much I believe in it. I’d bet my life on it.” He said, “Well, if you believe that strongly in it, I’m willing to pick it up from Quinn and Marlon, and I’ll make a deal with ‘em and put it out on Atlantic, and I’ll give you a finder’s fee of one point and I’ll put one of your songs on the B-side of it.”

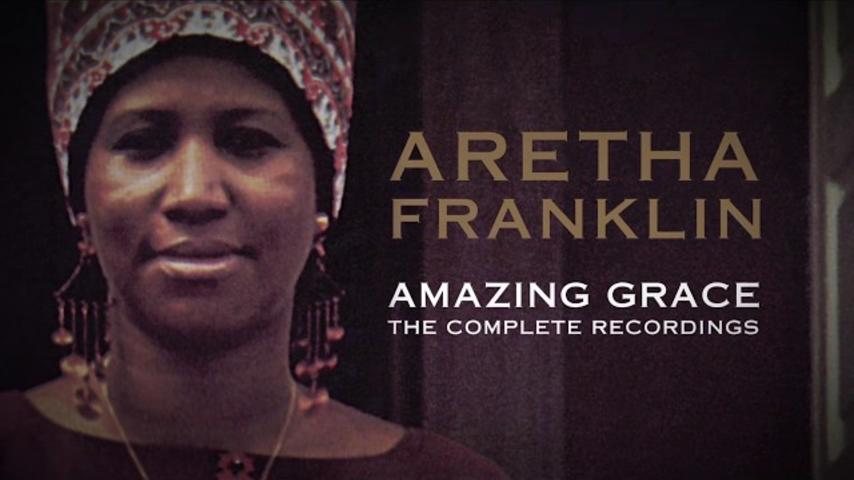

So that’s how the record came to be. But the mark of a great record producer, which you’ve got to understand, is this: can you take a brand-new act and go in the studio and cut a big hit record on that act? And I did that with Wilson Pickett, I did it with Aretha Franklin, I did it with Otis Redding… I did it with a lot of people, you know? [Laughs.] Clarence Carter’s “Patches.” Paul Anka, who hadn’t had a hit in 15 years, I did “You’re Having My Baby,” which was a million seller and went #1. So I’ve been good at my trade.

Do you have a favorite discovery from throughout your career?

Do I have a favorite? The Osmonds were one of my favorites. And Mac Davis was also one of my people that I felt very strong about. I did all the Osmonds’ first big records: “Go Away, Little Girl,” “One Bad Apple,” “Down by the Lazy River.” And then Bobbie Gentry, we had a big hit on her. Anybody who’s anybody that I’ve ever worked with, we’ve cut hit records. So that’s the name of that game.

That’s not a bad reputation to have.

No, it’s not! [Laughs.] Thank you, I appreciate that. Yeah, it’s a good reputation to have…especially in the record business!

You mentioned working with Aretha. What did she record in her first session with you?

“I Never Loved a Man the Way I Loved You,” which was her first #1 record. And the B-side was a number-one record, too: “Do Right Woman, Do Right Man.”

And how about Otis Redding? He was already somewhat established by the time you worked with him, wasn’t he?

Yeah, with Otis, we cut “You Left the Water Running,” which is a song that Dan Penn and I wrote together, and it was a hit. I mean, it wasn’t “(Sittin’ on the) Dock of the Bay” or “I’ve Been Loving You Too Long” or anything like that, but it was a big record for us.

You’ve cut a lot of stuff that’s continued to stand the test of time, but the stuff you did with Wilson Pickett is just epic.

Well, I’ll tell you, Wilson was one of my best friends, and we had a lot of success together. We had “Land of 1000 Dances,” “Funky Broadway,” “Mustang Sally,” “Hey Jude,” “Hey Joe,” and on and on. So we had a real run for our money. Pickett was one of my dearest friends.

Arguably the best moment in the documentary comes at the very beginning, when Keith Richards describes you as “a total maniac.” I mean, if that doesn’t paint you as the scariest man alive…

[Cackles.] Well, you know, I think he’s the scariest man alive! But I love him. I love all the guys in the band, but Keith is one of my favorites. He’s a producer also, you know. He did some sides with Little Richard and some other different people.

Was there anyone who you recorded that never took off the way you thought they would?

Well, there were certainly some I never gave up on, as you probably know if you’ve seen the movie. If I liked a song, I wouldn’t give up on the song, and I’d just keep recording it ‘til I got it right or I thought it was a hit. Some were hits, and some weren’t hits, of course, but I did better than average. I’ve got probably a hundred gold records and albums on my wall…so we’ve done something right down here! [Laughs.] And it’s been fun. We’ve had a great time. Of course, we do it different from anybody else. We don’t do the charts. We do it by trial and error. We just go in the studio with seven or eight musicians, horn players, and background singers, and we put it down. And if it don’t work, we change it, and we fix it. We might speed it up, we might slow it down, we might go to a different key, but we’ll do it ‘til we find what we’re looking for…and, you know, it’s worked out pretty good!