Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: America Worldwide

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

World Whirls

Circa 1960s, WEA’s labels, not yet united, had fellows who handled what was called “International.” Such fellows worked the rest of the world, mainly our licensees overseas. They had often flew across the Atlantic to look for remnants of acts that the Big Labels in Europe had left over. But mainly to pitch our un-licensed artists for native labels there.

Semi-annually, these WEA executives were treated lavishly, and their labels welcomed by their distributors in France, Sweden, Japan, wherever.

Slideshows of the labels’ upcoming releases were shown, tolerated til cocktails were served, often around 10 in the morning til the bars closed near midnight. Whichever way the deals went: whether they selling “our” albums in their lands, or “we” licensing locals acts for our land, International was a low percentage revenue plus dinner at some mansion in Majorca.

The Mediterranean isle of Majorca become an itch for us every July, when the Fall releases were previewed. There lived Charles Brady, a licensee for sales to the Army. Brady was gravel-voice. He sold tons of goods, from auto tires to condoms, to PXs around the globe. Warner Records got tossed in “for fun.” Brady paid Army buyers on the side, whatever it took. And on Majorca, next to a deluxe hotel called Son Vista, he’d built a mansion with 15’ ceilings, massive terraces, and two nifty daughters who failed to appreciate my wit.

After evening cocktails at Brady’s, our label gang slid back to the suite of Warner’s International fellow, Phil Rose, at Son Vista, awaiting the plane arrival of incoming, jet-lagged WBR execs Mike Maitland and Joe Smith, arriving after three days of little sleep, fueled by booze. Once they showed, from the suite’s balcony, Joe Smith gave a palms up wave (like the Queen of England) to the guests down on the terrace, who mistook his wave for a “come on up.”

A patio full of record execs from various labels overflowed up to the suite. Maybe 40 of them. So Smith called Room Service. Only one server working this late, not even a waiter. Maitland fell asleep on the floor. The only worker hauled “stuff to eat” up to the mad gang. Smith named him our “Head Waiter,” stood him on a stool, placed a crown of bananas on his head. We all sang “Guantanamera.” (That’s all I can remember ‘til we got to Paris.)

International Bonding Begins

Around 1967, our labels had begun setting up their own, pre-Kinney foreign companies. Warner set up its own label in Canada first, where the Canadian licensee (Compo) had repped the Burbank label’s releases in exchange for getting 12.5% of suggested list (minus tax). And then WBR in Burbank paid its artists from that. Compo got probably three times that amount. So, in ’67, WBR set up WBR Canada, and our new company began making profits after one month in the business up there.

Then, 1969, Warner set up its own label in London, run there by a charming chap named Ian Ralfini. Offices at 69 New Oxford Street. Ralfini was a name tough to remember for visiting artists. Clarence “Frogman” Henry, who flew in to Heathrow Airport with a frog on his shoulder, could never understand anyone’s name and called him “Iffen Ralfnic.” Forever.

But now Warner had its own office, 30 employees, and would sign local acts “for the world.” What a pitch – the world, by your one label! Fleetwood Mac and Small Faces signed on.

Across London, Atlantic’s Nesuhi Ertegun had that label’s own set up, run by a marketing bundle of energy named Phil Carson. Carson picked up rights to sell Virgin Records for three years, and Mike Oldfield’s Turbular Bells. Then AC/DC.

London was now “the place.” Signing acts “for the world” (not just North America) became a focus. Our labels would stroll London’s lanes, like King’s Road with its mod dress shops, clerked by emaciated girls who looked like they’d just come from a mascara tournament.

Label life in London felt ritzy.

Soon enough, Atlantic (via Phil Carson and the Erteguns) would pick up plenty of acts: Emerson, Lake and Palmer, King Crimson, Mott the Hoople, Yes, Screaming Lord Sutch and Heavy Friends. And, no small follow up this: distribute London-based labels named Rolling Stone, Clean, Embryo, Capricorn… All this via Atlantic’s own label, Atlantic’s to run and profit from. No WEA division. This was still “my-label-comes-first” time.

WEA International Begun

When Kinney International set up one distribution group under Joel Friedman for the United States, the next step was clearly “the rest of the world.” Its titan would be Nesuhi Ertegun, assisted by Warner’s Phil Rose (ex-Canada).

1970. Ertegun sets up what soon would be called WEA International, and divided management into two spheres. In charge, like some 16th Century Pope, Nesuhi drew a line down the Atlantic, straight down, so on the right side would be Europe and Brazil. That would be Nesuhi’s sphere. The rest, the left side, South America and those orient countries plus Australia, that would be Phil Rose’s sphere.

The two men were too smart to fight over territories. Nesuhi quickly told Phil, “Phil, you’re the best international exec in the business. Of course we’ll work well together. If we don’t agree, I’m the boss, and that’s the way it will be.”

On their first tour together, Nesuhi and Phil found themselves in a shared train compartment en route to Frankfurt. The shorter Nesuhi got the lower bunk. As Rose nodded off, he heard Nesuhi sum it up from below: “Phil, you know, yesterday we negotiated our first deal. Tonight we ate off the same plate. And now we’re sleeping in the same room, practically the same bed. Yes, I think it’s working out.”

London

But the three WEA labels were still not ready to sleep together and share incomes. When, in April of 1970, the new Kinney Music Group moved its three labels into WBR’s New Oxford Street offices. Ralfini now headed Kinney/UK, with Atlantic and Elektra packing up to move in. Each of the three labels resented being “Kinney-ized” in London. Rivalries got out of hand. The labels acted like bulls, it was mating season, and there was just one cow.

Ralfini struggled to handle it all. He reported to Nesuhi Ertegun and Phil Rose, but also reported to the U.S. labels’ three bosses. So Ralfini had five bosses to juggle, not counting Frogman Henry.

In 1971, each of the three labels had a system of “label managers” set up. Their own guys. Atlantic’s Phil Carson et al.

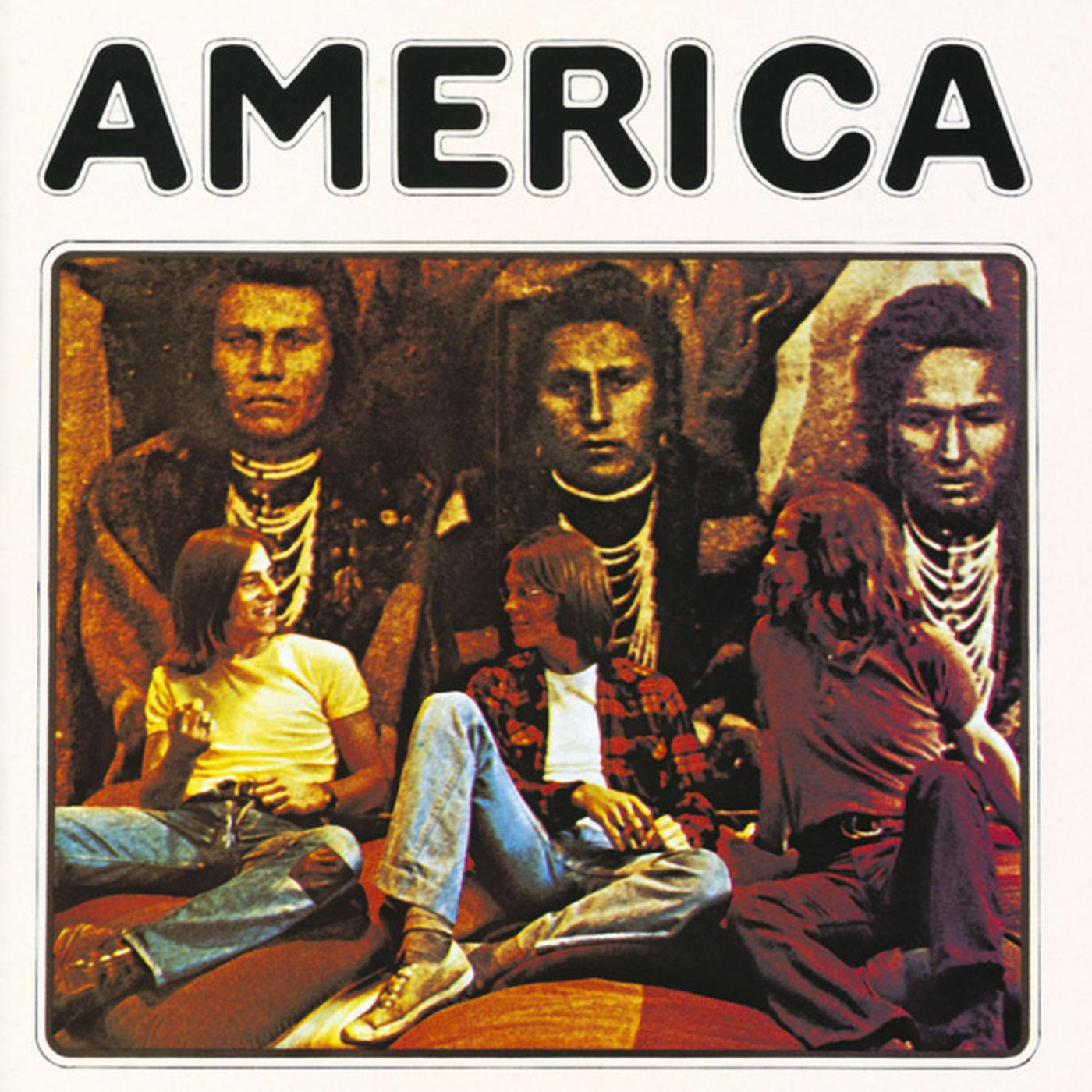

Knowing that Kinney was coming, knowing that Ralfini was his new boss, Phil Carson steered his latest discovery, a trio called America, away from Polydor over to Ralfini to handle the legal paperwork. To Carson’s shock, in March Ralfini signed America to Warner Bros. Records, worldwide. Carson, still on Atlantic’s payroll, had assumed America would go to Atlantic. It all felt like a family with three children, and one kid decided to eat the whole refrigerator.

Ian remained as aloof over all this as any dapper and funny chap can. He had to. Next year, 1972, he’d have Elektra to handle, too. At the welcoming party for Elektra there, mid-room, stood a welcoming cake, a yard high, with the company’s logos: Kinney, Atlantic, Warner, and … Warner again? No Elektra? Like some starved wildebeest, Phil gobbled the icing on one whole side of the cake, destroying logos so he could later claim that Elektra had tasted the best.

It was worth while. London had become, for the three labels and their parents, now known as WEA International, breadwinners.

Almost unexpectedly, the first act signed by Ralfini – America – caught on huge.

America Explodes

In Burbank, another act coming over from England, one with an odd name and no pop stars, was treated casually. They just sounded “yesterday,” like folk singers, acoustically on guitars, with no bam-bam. Maybe like early Cosby, Stills, Nash & Young? They trio chose the act name of “America” because they all were half-American (American Air Force fathers with English mothers) and they didn’t want to be considered “British musicians” just trying to sound American.

Ralfini’s roommate, Jeff Dexter, co-produced the trio’s first album. He also became America’s manager. The trio had originally wanted to record like The Beatles’ Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, but co-producer Ian Samwell talked them into “acoustic.”

One tune in their debut album, a song originally called “Desert Song,” immediately aroused audiences. Acoustic as could be. Soon, the song’s title was changed as the song became a massively-hit single by the group: “A Horse with No Name.”

Warners in Burbank issued the LP with the “Horse” side included. It was astonishing that this neo-folk trio (Gerry Beckley, Dewey Bunnell, and Dan Peek), barely out of their teens, scored #1 hits, then got a Grammy for Best New Musical Artist.

“A Horse with No Name” was ban by a few radio stations (even in Kansas City) because of suspected drug references, “horse” being slang for heroin. But for most, it was just irresistible hum along.

(A few critics lashed out at the lyrics. “Hardly poetic” said one lash. Lines like “The heat was hot” and “’Cause there ain’t no one for to give you no pain.” But such criticism didn’t matter to real people.)

On the first part of the journey,

I was looking at all the life.

There were plants and birds. and rocks and things,

There was sand and hills and rings.

The first thing I met, was a fly with a buzz,

And the sky, with no clouds.

The heat was hot, and the ground was dry,

But the air was full of sound.

I've been through the desert on a horse with no name,

It felt good to be out of the rain.

In the desert you can remember your name,

'Cause there ain't no one for to give you no pain.

La, la, la la la la, la la la, la, la

La, la, la la la la, la la la, la, la

And the album went platinum. In it was a second hit single: “I Need You.”

H-Word Albums Follow

Now quickly famous, the America trio decided to divorce Dexter and dismiss Samwell from their lives, and to relocate in Los Angeles. There their acoustic style got a little bit more emphatic, with L.A. key sessions drummer Hal Blaine on drums, and Joe Osborn on bass.

Their second album, Homecoming, came out in November 1972, and this time America was a star across the WEA globe. Top ten singles came out: “Ventura Highway” leading the way. Unlike other acts who’d started in the acoustic realm, America remained peaceful, easy-feeling, developing no tough sides, like Dylan or CSNY did.

For reasons hard to grasp, America decided to title its follow-up albums for Warner with words that began with “H.” As in Horse.

Next came 1973’s Hat Trick.

Then in 1974 release, America turned to George Martin, the producer of Beatles renown, plus Beatles engineer Geoff Emerick. Recording sessions no longer were just L.A. For Holiday, recordings took place in London (Martin’s AIR Studios) and down in the Caribbean at Montserrat. Singles came: “Tin Man” and “Lonely People” – both top ten.

Then album four: Hearts. Then Hideaway. Then Harbor.

Then off to Capitol Records.

London

And, back in London, where all this tripped-into prominence under Ian Ralfini, the moment for leaving home had come. WEA International stayed put, and handled the big business stuff. But the three WEA labels now set up their own offices: Phil Carson for Atlantic, Jonathan Clyd for Elektra, and ex-Beatles publicist Derek Taylor for Warner Bros.

For over-seeing Warners, Taylor chose a new office in Soho’s Greek Street. It was a downtrodden walkup, twelve meters wide, sandwiched in with the area’s falafel and porn shoppes.

But once more, all three labels were free to explode individually, and that they would do.

- Stay Tuned