Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Blind Faith

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

Ahmet and Stiggy Keep Going Steady

Rock groups broke up overnight in the ‘60s, but their managers held tight to their members. Certainly that was the case of Atlantic’s Atco label and Stigwood’s RSO. They had learned to represent individual artists’ careers, not just artists as groups.

As Cream was breaking apart, as the Bee Gees were losing their brotherhood, Ahmet Ertegun and his London-based cohort Stiggy treated their artists like misbehaving young family members.Their family.

Step back to 1968 for this:

In New York, Ertegun was getting ready to send Stiggy part of a new, American act that Atlantic had signed. Three guys again, but this trio had to sever their past ties to their latest bands.

In Ahmet’s office now sat Stephen Stills, ex-Buffalo Springfield but now feeling his way to a group with David Crosby and Graham Nash. At this time, Stills nor Crosby nor Nash had management in England. And Nash was even living over in England. Stills needed to talk about English management with Nash, but couldn’t even afford the plane fare.

“Management in England?” Ahmet reached in his desk drawer and gave Stills $2000, cash.

“Go see Robert Stigwood,” was his instruction.

Stills flew over to meet Stigwood. On the way by London cab to the meeting, Stills had seen a Rolls-Royce in a showroom window. Liked what he saw. Right away, mentioning that to Stigwood, Stills said, “Can you have it delivered to me tomorrow?” Stigwood suggested that they should first have a business agreement.

Stills protested, “But Ahmet said we’d be good together.”

Stigwood answered right out. “I’m not that good,” he protested.

The deal for Stigwood’s management did get made, however.

To Two Parts Cream, Add …

Meanwhile in London, after the break up of Cream, two of that group’s three stars had also felt like a new super group might be good, for them. But they felt like making a foursome this time. Adding Traffic’s Stevie Winwood on lead guitar, that sounded good. Traffic had just split up, and Winwood was jamming with Clapton in Eric’s basement in Surrey.

It was only nine weeks now since Cream had split apart, and in that split, Clapton had promised Jack Bruce, the main leaver from Cream, that if they ever got back together again, Bruce would be re-included.

“No,” Winwood kept saying, “we need Ginger.” Clapton was torn. He knew there was on this Earth no more talented drummer than Ginger Baker.

So “yes” to Ginger Baker. And just skip by Jack Bruce.

By May of 1969, they added Ric Grech on bass; Grech leaving Family to join. But Jack Bruce, gone, left to his own solo career.

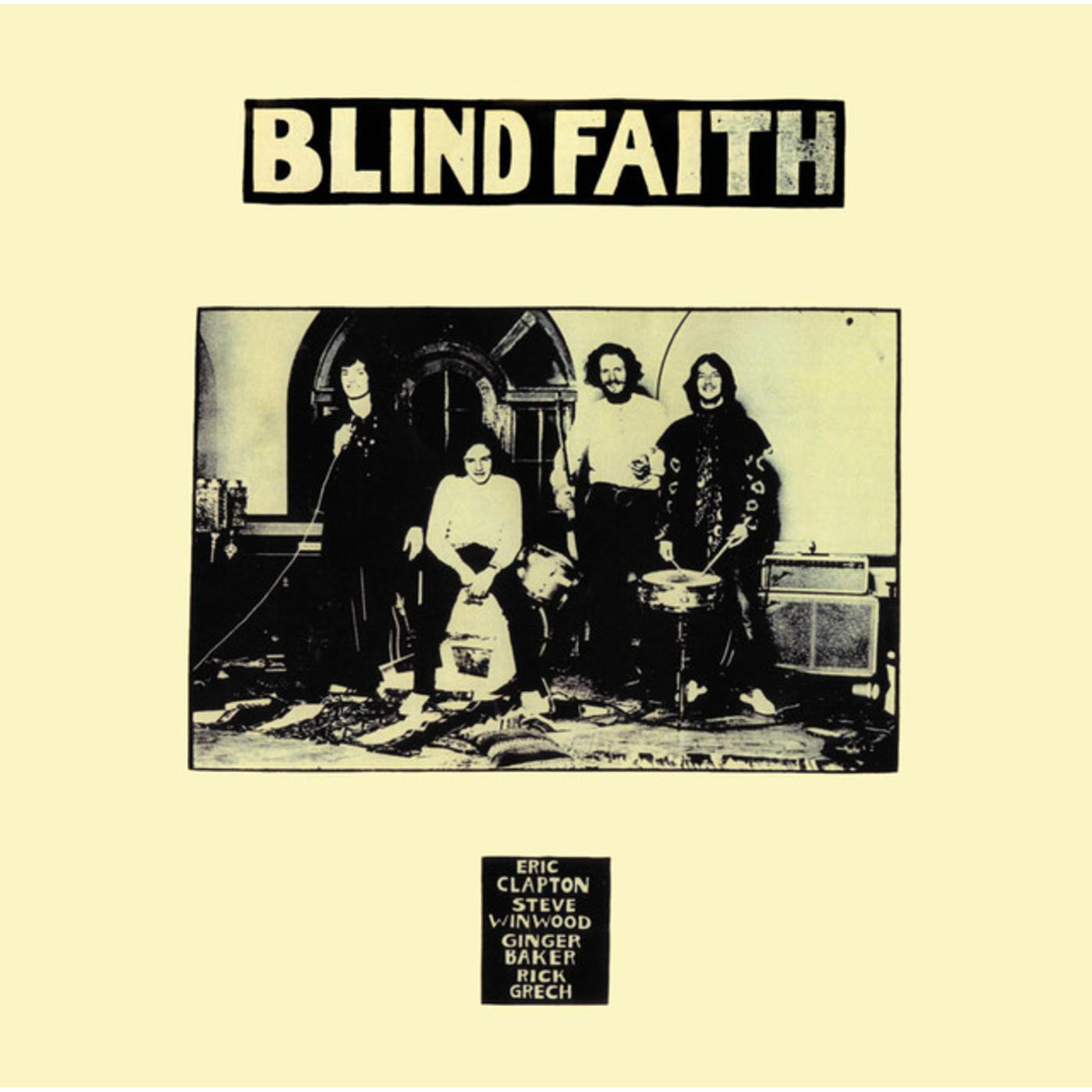

The foursome considered a new name for their new group, even as the trade gossip was buzzing over them as the new “Super Cream.” But now there was no question about which the group’s label(s) to be. Winwood, was still signed to Island, but he’d get leased to Atco, so Atco became the label for Blind Faith after all. Stigwood agreed, after all.

Naming the Fresh Cream

Living at Eric Clapton’s flat in Surrey was another long-time pal, a photographer named Bob Seidemann. As artists, they hung out at The Pheasantry Studios on King’s Road in Chelsea. There were other ravers living there, too, like psychedelic cover artist Martin Sharp, who’d painted the Disraeli Gears cover for Cream. Plus assorted girl friends. But Seidemann had his own special place: he slept on a ledge under a skylight in the living room.

Seidemann had moved out to a different basement flat, with another bunch of ravers in Surrey. There, Stanley Mouse, another San Francisco poster artist, lived too.

Seidemann had come from San Francisco, where he’d gone deep into Haight Ashbury, photographing the Grateful Dead, and Pigpen’s girl friend, Janis Joplin. Seidermann imagined deeply, and at one point had taken photos of Janis in the nude.

Seidemann’s phone rang. A call from Robert Stigwood’s office. The caller asked if Bob would be interested in shooting an album cover for Clapton’s new group. No name yet.

Seidemann knew this was “big chance” time. Knew that the Western World had adopted a new religion: and Clapton might be its golden calf.

Seidemann’s San Francisco Vision

Let me quote how Seidemann expressed in acid-based prose how this offer from Stigwood’s aide felt:

“Technology and innocence crashed through the tatters of my mind. Only a thread of an idea, something I couldn’t see, something out there just beyond my vision, an impulse rippling through the interstellar plasma. I stumbled through the streets of London for weeks, bumping into things, gibbering like a mad man. I could not get my hands on the image until out of the mist a concept began to emerge. To symbolize the achievement of human creativity and its expression through technology, a space ship was the material object. To carry this new spore into the universe, innocence would be the ideal bearer, a young girl, a girl as young as Shakespeare’s Juliet. The space ship would be the fruit of the tree of knowledge and the girl, the fruit of the tree of life.”

End quote.

Finding His Juliet

While Clapton’s group was jamming and learning new tunes, photographer Seidemann rode the London Tube to Stigwood’s office to explain his revelation. On that ride, the tube door opened and “she” stepped into the car, a pre-teens girl wearing a school uniform, plaid skirt, white socks. To Seidemann, this girl felt buoyant and fresh as the morning air. Like his Juliet.

He asked her if she would like to pose for a record cover for Eric Clapton’s new band. Hearing the word “Clapton,” everyone in the car tensed up, Seidemann recalled. The girl asked him, “Do I have to take off my clothes?” and he answered “Yes.” He gave her his business card and begged her to call him. He promised to ask her parents’ consent if she agreed.

After his meeting at Stigwood’s, Seidemann learned from Mouse that “she” had called and left her number. With Mouse’s help, a photo layout was made, and together they headed out to meet the girl’s parents.

The family lived in Mayfair. Swanky. Her parents were worldly and bohemian. They even knew Alan Ginsberg. After they heard Seidemann and Mouse’s presentation, they agreed. But the 12-year-old girl on the train was still feeling shy.

Her younger sister, age 11, begged: “Oh Mommy, Mommy, I want to do it,” and Seidemann felt this younger, 11-year-old was even better for this shot. Seidemann compared her to Botticelli’s angel in innocence.

She said for her fee, she wanted a young horse. Seidemann explained that the record business paid in pounds, not colts. They settled on ₤40.

Through all this, Seidemann realized what the photo he envisioned represented. To him, he believed it represented having faith about the future, even if that faith had to be blind.

Creating the Album

Eric Clapton was slow to tell the world about what his new group was recording. He’d say it was “his” new album. He didn’t have a name for it even.

During 1969, the group practiced on, but it wasn’t until Spring that they got serious: they moved their performing into Olympic Studios, in SouthWest London. Olympic had been home for many rockers in those days, recording acts from the Beatles (“All You Need Is Love” to Jimi Hendrix (“Are You Experienced”). And on and on. The place to record.

Winwood and Clapton hired Jimmy Miller as their producer. Miller had strong credentials: he’d produced two albums for the Rolling Stones (Beggar’s Banquet and Let It Bleed) and three for Traffic (with Steve Winwood). And Miller had once been a drummer, too. His cuts felt that way.

By now, Clapton had embraced the phrase “Blind Faith,” as first spoken by Seidemann; Clapton thought it summarized his outlook on this new group, which was already getting famous to the rock crowd from its stars, even without a “band name.” To name the band, Blind Faith stuck.

Their first performance in public was in London’s Hyde Park (June 7, 1969). The crowds jammed in there, cheering nearly everything.

Watch the Hyde Park concert here:

At Olympic Studios, recordings continued, until they wrapped up their album on July 24. Clapton again felt misgivings about this approach; the group was reminding him of the “Super Cream” that he wanted to avoid, free from more of those fan riots during their live shows.

But “done” it was, and time for its release.

America First

The band, now clearly promoted as Blind Faith, made its U.S. debut at Madison Square Garden on July 12. Showing up were more than 20,000. Good start. The band then toured for seven more weeks across the U.S., ending up in Hawaii on August 24, 1969. Audiences loved it all, even though Blind Faith often played its pre-Faith hits, mostly older songs by Cream and Traffic, familiar tunes that crowds cheered.

The day they finished in Hawaii was the day their album came out. On its cover, it had no name. No words, no logo, no album number even. The LP quickly topped both the UK and US charts as #1. (It even went to #40 on the Black Albums chart, an amazing achievement for a white rock quartet from England.) The album sold over 500,000 copies in the first month out, and made Atco smile.

The cover made great impact:

Controversy? You betcha. On the cover, no title, but other features certainly got attention.

At Atco Records, showing the cover to retailers turned embarrassing. Despite the whopping sales, Atlantic needed a different cover to get into mom-and-pop shops. With no help from the artists or the photographer, Atco quickly put together its alternate:

Eric Clapton put his wah-wah foot down. He would not allow this total change of album cover. He liked the girl shot. Ahmet suggested a way out. A deal got made: Atco could sell both. Or either. Let their retailers choose.

But the cover buzz grew louder. Who was that nymph?? Rumors like she was Ginger Baker’s illegitimate daughter. Like she was a groupie being held captive by the band members.

Speculation arose. No one would tell, certainly not the photographer, Bob Seidermann. He’d promised to keep quiet, and did. For 40 years.

Then, decades later, photographer Seidemann and the girl appeared. Out came the truth: her name is Mariora Goschen. She’s now in her fifties. She’d been a computer programmer. She now lives back in London, where she works as an alternative therapist, practicing shiatsu massage, acupuncture, and breath therapy.

When asked about her life, since Seidermann had taken only five minutes of it to shoot the shot, Mariora has answered, “At the time, I don’t think I was even aware that I had any breasts.”

And she added, “By the way, I’m still waiting for Eric Clapton to ring me about the horse.”

-- Mariora Goschen, too, wants to Stay Tuned

Where Are They Now

Bob Seidemann: Still selling photography, now located back in San Francisco.

Eric Clapton: Recently celebrated his 50th anniversary as a pro musician, and still touring. He’s the only three-time inductee in the R&R Hall of Fame.

Steve Winwood: Now lives in Nashville, plus has a manor house in the Cotswolds. Still performing: In 2007, he joined Clapton at the Crossroads Guitar Festival, where the played two Blind Faith songs.

Ric Grech: He retired from music in 1977, and died in 1990 from kidney and liver failure.

Ginger Baker: Still alive and independent, often into African music now. His influences on rock drumming (two bass drums, etc.) have made him “rock’s first superstar drummer.”