Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Getting Heard

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

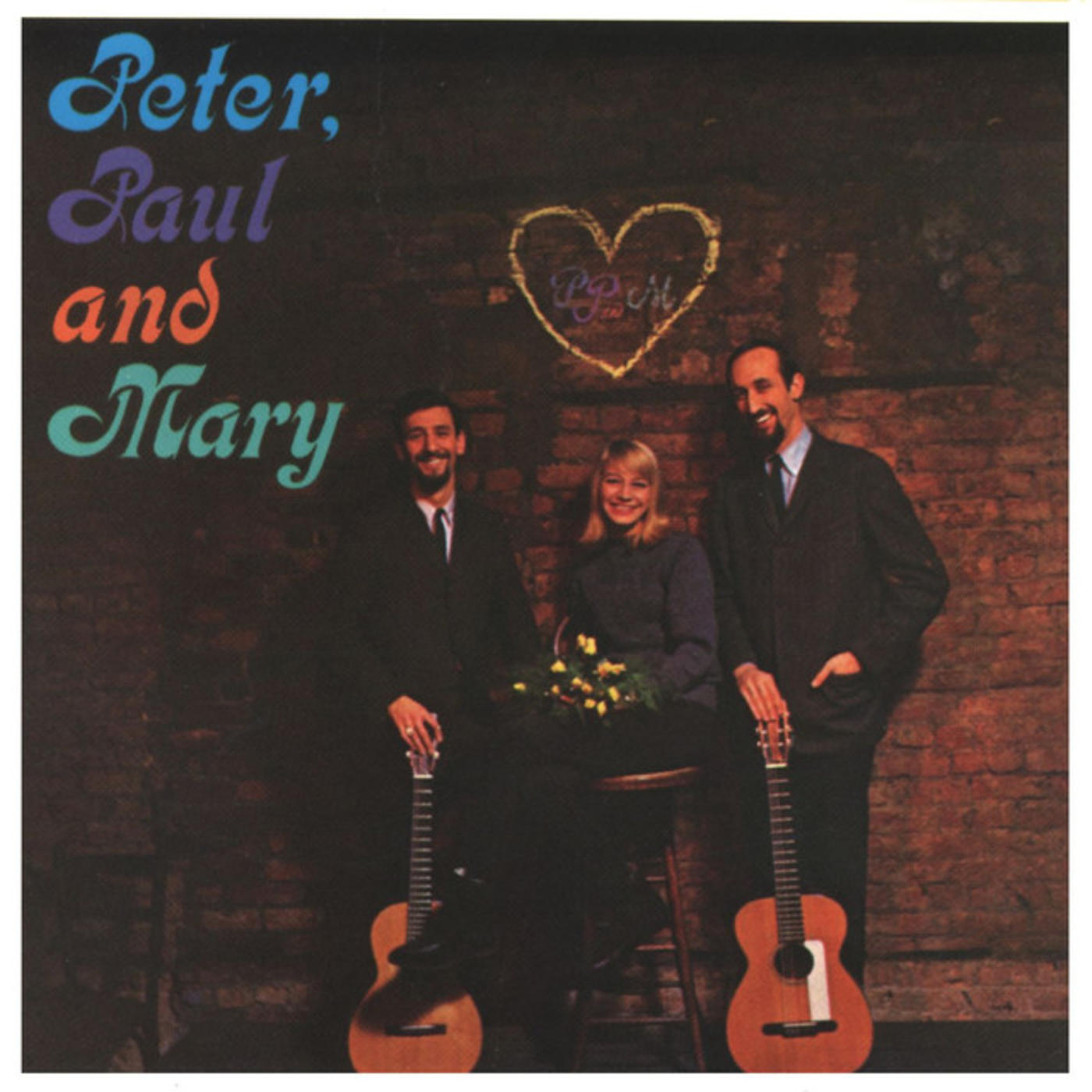

The morning after Mike Maitland got the phone number he should call, he called. He connected with that Albert Grossman, who had this trio for sale. He’d assembled them, rehearsed them, kept them out of New York until The Bitter End. His super-wish: he’d create, record, and manage a folk song group with sex appeal (more than, say, Pete Seeger and all those folkies). He had cast his trio carefully.

“They go by their first names,” Albert insisted: “Peter, Paul and Mary, in that order. Let’s meet at 11, my office. 58th Street.” Maitland said he’d be there.

Grossman got in touch with his co-pro’s: With publisher-in-heat Arlie Mogull, even though he’d stayed home the night before. Still, Artie knew hype: “I saw this group last night at the Blue Angel, and they’re the greatest goddamn folk group ever! They’re great.”

That word passed from Mogull out west to Warner music publisher Herman Starr (no relation to Ringo). “The Greatest,” Herman heard. Starr then dropped the “greatest” word at lunch to Jack Warner.

All this out of Maitland’s earshot. Eleven a.m. in New York now, and it’s time for Maitland to deal with Grossman. For Al: His kind of deal. He sat across from a buyer, and Grossman held all calls (including an interest in the trio from Atlantic Records, as backup). Grossman outlined terms:

Peter, Paul and Mary would have artistic control: meaning they’d record what and how they wanted, create their own packaging, and get $30,000 to start a five-year deal. That for a trio who’d been together about one week, and had six songs total.

Maitland and Grossman shook on it.

Herman Starr, hearing about that handshake, was furious. “You’re supposed to check with me,” he barked at Maitland. The deal was a deal, though. Peter, Paul, and Mary started recording, not for the usual four sessions that create most albums; instead, for a cost of $55,000, and for months. Then more months. Peter, Paul, and Mary had full control. Grossman stood strong, as ever he would. He also kept his act from getting pestered by that label out there.

In Burbank, the completed album stayed on the company’s upcoming release schedule until it felt like “whenever.” No one from Burbank visited a recording session.No one from Burbank was invited even.

Joe Smith Creates Radio Promotion

Meanwhile: a new skill grew in Burbank in 1962: radio promotion. Up ‘til now, Warners had put out “white labels” (free records for radio play) usually through indy distributors who had tons of labels to handle.

Joe Smith, who’d been a top DJ before, added doing it his way. He contacted the few promotion men WBR could rely on, and pushed what Joe’s ears felt warmest to. Some acts were just one shots, but even those were better than blanks:

Emilio Pericoli (“Al Di La”). Saverio Saridis (The Singing Cop sings “Love Is the Sweetest Thing”). Joanie Sommers (“Johnny Get Angry”). Like them, play them, sell them.

Warner Bros. now stopped selling its soundtrack albums to others labels, and 1962 brought out The Music Man and Gypsy. But then, when Peter, Paul, and Mary finally brought out “If I Had a Hammer” and more “folk” songs (many by Grossman-managed Bob Dylan) that release made Joe Smith gush. San Francisco became Joe’s nativity scene. There, a kid named Don Graham had been doing promotion since the Fifties, and had held sway there through Warner’s near collapse under Jim Conkling. He’d shipped out combs when Kookie became a single. He’d heard how radio promo worked back when Payola had become a word for “pay” and “Victrola.” Graham added energy to Warner’s “could be” records.

Joe Smith backed Don Graham avidly.

When Don Graham got hold of “If I Had a Hammer” as a single, then the full album, he plastered the inside of a tunnel on Route 101 with stickers of Peter, Paul and Mary’s name. When the trio came to San Francisco’s club The Hungry i, Graham induced local college kids to stand in line for tickets, picketing the club to have PP&M play a second week. When WBR didn’t put out the right single, Graham made four acetates of “Lemon Tree.” He took them around to KEWB and lied, “Here’s the new single from Peter, Paul & Mary. Exclusive!”

Then he gave exclusives to three other stations.

When WBR started getting big re-orders for the album with “Lemon Tree” from San Francisco, Joe Smith called to phone-hug Graham over breaking the album.

“No,” answered Graham, “they want the single.”

“There is no single.”

“There’d better be,” Graham told Smith. “Quick.”

“Lemon Tree” bore fruit. It spent seven weeks as #1 on the charts. Then the album took off. The album was Top Ten in Billboard for ten months. For Warners, the LP eventually sold two million copies. Not bad for a folk music album.

In San Francisco, painting inside a tunnel had worked.

Promotion Can Run Deep

In Burbank, the energy coming from promotion was starting to work, more and more. Singles were the sparks, but when they lit up albums, sales fires could roar.

Peter, Paul & Mary kept going:

1963: “Puff, the Magic Dragon” in Moving. “If I Had a Hammer,” sung at Martin Luther King’s Civil Rights March alongside his “I Have a Dream” speech.

Then a rush more from 1963's In the Wind: Bob Dylan songs like “Blowin’ in the Wind,” “The Times They Are a-Changin’,” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s All Right.”

Albums flowed slowly, eventually a release that apologized via its title: Late Again.

Then 1969: “Leaving on a Jet Plane,” their final Top 40 hit arrived in the album 1700, along with “I Dig Rock and Roll Music.”

Whether PP&M truly dug Rock and Roll Music, hard to tell. The group, however, broke up in 1970, each going his or her own ways.

Then, after eight years of solo-ing, they reunited in 1978, and worked concerts and made albums but at a slower pace. And they stuck on Warner Bros. Records, all the way to the next century.

But that first year, 1962, had been the heart-thumper. Now what? The staff had a bigger wish, that no longer would Warner Bros. Records get hammered by those studio music execs. But to get that freedom, WBR needed more than Peter, Paul and Mary.

Joe Smith’s second big signing was about to become that “more.”

For that next big step, Stay Tuned.

Where Are They Now

Peter Yarrow in 1969 married Mary Beth McCarthy, daughter of 1968 presidential candidate Eugene McCarthy. He has remained politically active life long, heading Operation Respect. He has appeared on 61 different albums. He lives in Telluride, Colorado, and sometimes records with his daughter, Bethany, and son Christopher.

Paul Stookey (who off-stage preferred his first name Noel). He’s the tall one. He and his wife Betty married in 1963, have three daughters, and now live in Blue Hill, Maine. Noel, back in his thirties, adopted born-again Christianity. He composed “The Wedding Song (There Is Love)” in 1969 as a wedding gift for Peter Yarrow.

Mary Travers, during on-their-own times, she recorded solo albums, four out of five of them for Warners in the early 1970s. She married four times (three divorces), and died in 2009 of leukemia, age 73.

Don Graham has remained in radio promotion all these years, and continues now from his home in the Hollywood Hills, where he heads a company, Progressinve Music Marketing that handles “adult standard radio.”

Al Grossman died of a heart attack back in 1986, en route to London on the Concorde to sign an unknown singer. Grossman through his professional career was known to be a “breadhead,” moving quietly but with strength to making the right deal. He had signed Bob Dylan to major deals, founded Bearsville Records, and managed such artists as Todd Rundgren, Odetta, John Lee Hooker, Ian and Sylvia, Gordon Lightfoot, The Band, Jesse Winchester, and Janis Joplin.

•••••••••