Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Learning to Fug

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

1967, in the East Village, walking one evening downtown with Mo Ostin and the major-sized and connected manager, Al Grossman, we’re headed for a small club. Al’s long hair in a pony tail. He smokes originally: his cigarette held between his ring and little fingers, the rest of his hand curled into a smoke chamber, inhaling with big pulls through the hole between his thumb and first finger.

I recognized his inhaling technique as this year’s epitome of pop-hip culture.

It’s after dark. Mostly it’s Al talking about this act, and we must look dangerous. Because from some upper story window, somebody tosses an egg at Grossman.It hits his shoulder, splat, but Al does not even notice. He’s into business, making his point, that’s what matters. More important than some old egg.

Mo’s in New York, I’m tagging along, looking for acts for Reprise. Not in this toddling town as usual, because he and I are Burbank-based. But recently, our colleagues in competing labels, like Atlantic and Elektra, have been focusing away from New York. Atlantic to England; Elektra to L.A.

Grossman we’ve known for some years now, since the birth of Peter, Paul & Mary, “his act,” managed by him, signed by Warner. Author Michael Gray, in his bio of Bob Dylan, described Grossman gravely:

“He was a pudgy man with derisive eyes, with a regular table at Gerde’s Folk City from which he surveyed the scene in silence, and many people loathed him. In a milieu of New Left reformers and folkie idealists campaigning for a better world, Albert Grossman was a breadhead, seen to move serenely and with deadly purpose like a barracuda circling shoals of fish.”

For Mo Ostin, Grossman was a valuable connection to music makers in New York. Ostin and the Reprise label now knew Los Angeles, Las Vegas, Palm Springs, but had little to do, so far, with the dark Villages of Manhattan. Grossman knew them, every little club. Every trio, good or lousy.

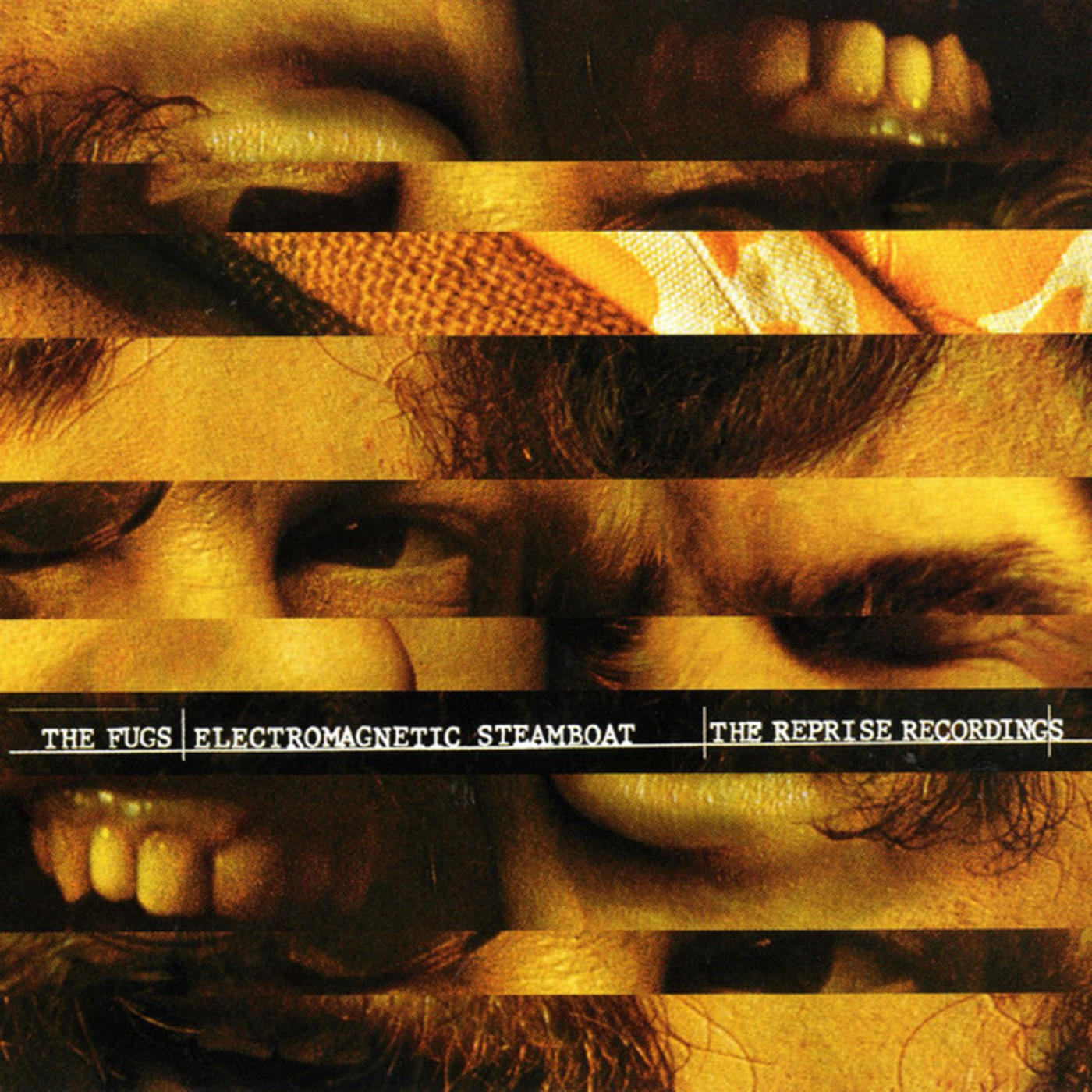

One such trio had adopted a shocking pseudonym: called themselves The Fugs.

Early Fugs

Grossman had been aware of The Fugs for several years. The group had many short term members, but is best recalled for its seminal trio: two poets plus one drummer, and original combo.

The poets were Ed Sanders and Tuli Kupferberg; the drummer was big Ken Weaver. They began as Fugs in 1964, trying to tour and sell records, but living in New York slums. Partying where they lived with Hendrix and Zappa. On the road, promoting their music via Fugs T-shirts (high point: giving one to Kim Novak).

And now, Al Grossman knew they might have a finished an album that the sponsoring label’s corporate bosses might want to reject, for corporate reasons. To potential buyers, “Fugs” sounded dirty.

One of those wary bosses was at Atlantic Records’ Jerry Wexler, and at this time, Atlantic was negotiating its own buy out by Elliot Hyman and his Warner 7 Arts company. Atlantic worried that being known as a label with The Fugs under contract, eeek, might lower its sales value to Big Warner.

The Fugs had first cut a demo for Wexler, then signed a deal with Atlantic. They delivered their album to Atlantic, going up to Atlantic’s offices to play it through. Not much reaction. Little comment, other than Wexler telling Ed Sanders “Good production job, Ed.”

A few days after that meeting, Atlantic’s Jerry Wexler called Sanders at home and said, briefly, that Atlantic was not going to release the album, and that The Fugs were off the label.

The Fugs were stunned. What now? Their album? They left on a tour of love fests from San Francisco heading back east. Concerts where those out front carried peacock feathers and wands of burning incense. The Fugs toured and each morning felt zonked.

Socially, they were no longer Beatniks. They were now Hippies.

Al Grossman turned to Mo. About that album? he asked.

Would Mo be interested?

The Fugs on Reprise

Mo Ostin was the kind of label guy who believed in you. And if he believed in you, you got your way.

The Fugs got four albums their way. With no censorship from Reprise.

Tenderness Junction (Reprise album #1)

First, of course, was their already done-for-Atlantic Records, now switched effortlessly over to Reprise. With no tremors from any corporate deal in the way. (Reprise’s owners had asked only that Frank Sinatra, then a minority owner of Reprise, sanction its release on Reprise. So Mo Ostin sent Sinatra a copy. He gave it his OK.)

By now, The Fugs had more members to its core trio, and added guest poets like Allen Ginsberg, and once a sitar player. But it was still rock about sexual freedom, psychedelic freedom, and anti-war.

Songs like “Turn On, Tune In, Drop Out” became an anthem for psychedelics, while “Wet Dream” parodied the teen, Platters-style love songs, in which romance was the Queen of the Prom, sitting on her throne (“sitting on my face”). Anti-war got promoted on “Exorcising the Evil Spirits from the Pentagon Oct. 21, 1967.” Recorded live.

1968: It Crawled Into My Hand, Honest

The Fugs’ most expensive album (cost $25,000 to record) cane next. Again, diversity of the cuts in the album. Psychedelic rock like “Crystal Liason.” Short tracks, like “National Haiku Contest” depicting a teen’s unwanted pregnancy, and “Robinson Crusoe” (sexual frustration between Robinson and his Man Friday). Redneck satire in “Johnny Pissoff Meets the Red Angel.”

The Fugs entertain using their deep beliefs.

Getting Attention from Burbank

By now, Reprise Records had become devoted to sticking with its “underground” acts. They’d signed Jimi Hendrix, and Frank Zappa, not to mention what got called “hippie” music from lands like Laurel Canyon.

Reprise and Warner Bros. Records showed its pride in these slower-selling “rebels” by running distinctive ads in the underground press (like Los Angeles Free Press, as one of dozens such hip papers across America).

Mo Ostin liked ads like these, and we wrote many for our “up and coming” (hip) acts. Mo never asked to censor a word. His inner motto as CEO was “write and sing whatever you like.” The Fugs appreciated Mo’s attitude, while we at WBR lived it fully.

The ads got attention. Hot headlines, then sassy body copy you had to squint to read:

Imagine: a dream date on the town with your favorite Fug, and all that can imply. It could be yours.

Just tell us what you think of the latest Fugs album, “It Crawled Into My Hand. Honest.” In from one to 100 words. Or more words, if you insist. Or, if you’ve got something classier than words, fair enough.

We of course reserve the right to make up more rules as we go along. But for now, that’s all. This is a pretty loose contest.

Along with your entry, be sure to name your fave Fug, the one you want for your once-in-a-lifetime Dream Date. We’ll plow thru the mail and then let you know if you’re the big winner. Honest. Even if you don’t win, your chances are pretty good: the 99 runners-up will get a free copy of the next Fugs album, whenever that’s ready.

Fugs Get Pooped

The Fugs had become a matter of pride at Reprise.

Two more albums came out on Reprise, including Golden Filth, recorded live at the Fillmore East.

Reprise had stood by its Fugs, but by now, the group itself had “had it.” Tired of being picketed, of bomb threats, of getting arrested. The Fugs’ four years seemed, to member Ed Sanders, “like forty.”

In February, 1969, The Fugs gave their final concerts at the Vulcan Gas Works in Austin, Texas. They would not perform for the next 15 years.

Sanders packed up boxes of concert tapes and paid no attention to them for 25 years.

Then, the best of The Fugs got rescued on CD. And no one got arrested. So far.

-- Stay Tuned