Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Mike And Mo Go Toe To Toe

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

Let’s start this back around 1960. Mr. Sinatra had just hit a big movie, Ocean’s Eleven, set in the casinos of Vegas. Oceans starred not only Sinatra but also Dean Martin, Sammy Davis Jr., Peter Lawford…all clan-types, acting on screen like utter rascals. A box office whopper.

After both producing and starring in Ocean’s 11 for Jack Warner’s studio, Frank Sinatra was all the movie-town buzz. Oceans had cost $4 million to make, then brought in $10 mil to Jack Warner’s cashbox. No wonder Warner wanted Sinatra “on his lot” for future film making deal. Warner loved that kind of math.

Frank liked winning like this. Felt fine to be in charge. Win all arguments.

He proved that before, big time, when he signed an exclusive contract with his third record label. (He’d already been through RCA, then Columbia. He’d already listened to A&R titans like Mitch Miller, who’d persuaded this young song star to record trash singles like “Mama Will Bark,” in which Sinatra both sang and barked with the stunning-looking starlet Dagmar. (See below! We’ll wait.)

But by 1960, Sinatra’s career had advanced. He was in Hollywood, living there up on a pricey hill. He’d married very well (Nancy for 12 years) with whom he had three Sinatra-kids. And then with Ava Gardner for six years. Or so.

He’d produced a movie, but never his own records. And he itched to produce records…his way. He even wanted his own label, so that he and other singers (more than an Ocean’s 11 of them), so that good singers didn’t have to obey nuts in suits.

But Capitol has him under contract, and is picking the tunes, hiring the back-up bans…. Not “my way.”

So what’s a contracted-to-Capitol as an “exclusive singer” going to do?

Hoarse-ing Around

Sinatra’s Capitol deal was exclusive. For seven years. Signed in ink. But come 1960, Sinatra wanted his own label. A big label. For him and his “pallies,” as he once put it. His own label became the “only” way he’d get bigger, last longer, wake up in charge of his life. In the world of records, Frank wanted to strut.

And he figured out how. He’d tell Capitol, “I just can’t sing. I’m hoarse,” he’d whisper to them, hand to his throat. He whispered to Capitol from 1959 to 1960.

A call was sent from Warner to Sinatra’s “agent” (which is really too wee a word for…) Mickey Rudin, maybe the #1 Power Attorney to Hollywood stars, from Lucille Ball to the Aga Kahn.

For Sinatra, Rudin was his “fixer.”

Photo courtesy Mary Carol Rudin Frank Sinatra and Mickey Rudin

“Fix Capitol,” Frank told Mickey.

Mickey arranged a trade off. Sinatra would get soundtrack rights for a new movie, Can-Can, if Capitol would allow Sinatra to be NON-exclusive. That worked.

Next, Rudin tried buying a label for Sinatra to own. All his own. Jazz label Verve was up for sale but – oops -- MGM got it. Sinatra decided, “Let’s start from scratch.” From the Verve meetings, they admired and they hired an ex-Verve exec named Mo Ostin: a UCLA graduate in Finance, who wore glasses, had a respectful brain, and liked talent.

Mo signed up with Sinatra’s company, because it fit him well. From the owner/seller of Verve, Norman Granz, Ostin had learned how to treat talent. Five ways, and those five suited Sinatra’s aim to build “a better mousetrap.”

How to Deal with Talent:

• Listen to them

• Ask them lots of questions

• Accept who’s the boss

• Wait your turn

• In the recording studio, leave them alone

Frank chose the new label’s name from a list he’d asked for. He liked “Reprise,” meaning to hear and hear again. Sinatra pronounced it “reprise,” like reprisal, and pointed in the direction of the Capitol Tower, up Vine Street.

Reprise opened its own office: just a second floor over a Pacific Radio store, mid-Hollywood on Cahuenga Blvd. Ostin became manager of Reprise, under, clearly under Sinatra. And Rudin.

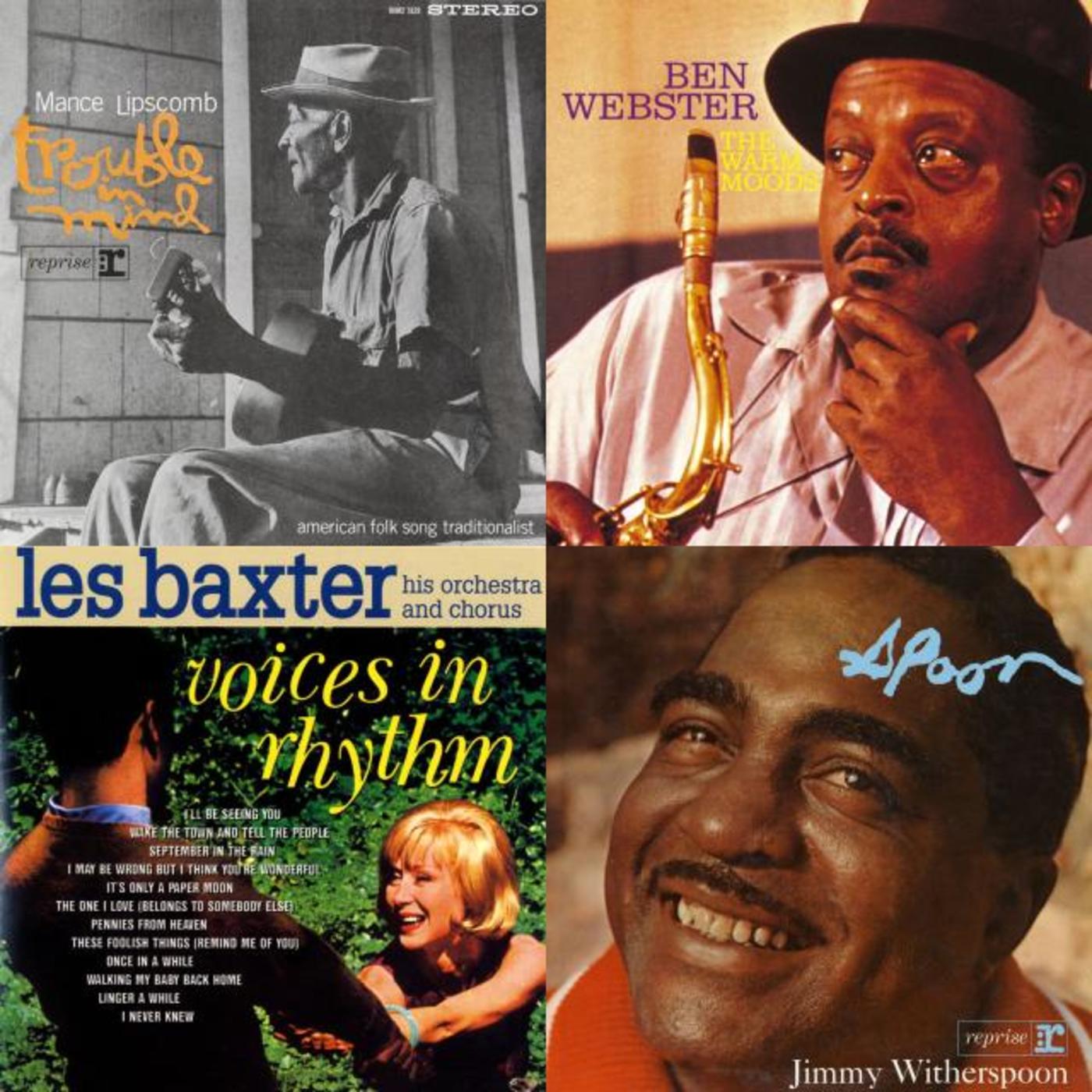

First Releases

Capitol had not forgotten its “semi-exclusive.” It urged Sinatra to sing some for their label. Sinatra kept stiffing “those bastards.” When going through songs for his albums, Sinatra would, upon finding a lousy song, put in Pile X, saying “Let’s save that one for the Capitol record.”

Sinatra was late in delivering his albums to “up the street.”

And then when “now” came, Reprise ready to debut in the market, it took out trade ads shouting how Sinatra was now singing “free, emancipated…” and so on.

To play it equal, the sales chief at Capitol, Mike Maitland, timed a sales deal for the same moment Reprise would issue its first Sinatra album, called Swing Along with Me. Capitol sued Reprise, claiming the album Capitol had heading for the market was being called Come Swing with Me. L.A. Superior Court’s judgment: Reprise was prevented from using the words “With Me” on its album.

So Reprise adjusted, and out on February 13, 1961, Ring-a-Ding Ding! (It got to #4 on Billboard chart.)

At Capitol, Maitland buried the Reprise debut. He had Capitol marketing come up with a “two-fer,” where stores and patrons could get two Capitol Sinatra albums at half price: $1.98, while Ring-a-Ding Ding!’s list price was $4.98.

Soon enough, there were 12 Capitol Sinatras on the chart, plus one from Reprise. This was no honeymoon that Mike Maitland had set up.

Reprise Becomes a Three-Year Struggle

Dean Martin came over to Reprise (from Capitol). Sinatra’s pallies from Palm Springs (the Dinah Shore crowd, they gladly sang for Reprise.

It didn’t work. Sales on Reprise albums: under 20,000 each. Sinatra held firm: no rock ‘n’ roll. Mo Ostin later recalled, “The only thing that was meaningful at Reprise was the kind of music Sinatra had been involved in all his life.”

The accounting (done by Murray Gitlin, a college chum of Mo Ostin’s) revealed rotten results. When Gitlin added and subtracted at the end of Reprise’s first year, he had reported that in 1960, Reprise had made $100,000. But that was with no albums actually released; you know how accountants talk.

It would be the last good news Gitlin reported. At the end of 1961, the Reprise books showed, oops, minus $400,000.

Sinatra kept recording. But sales were oops-ville. Sinatra strayed off, now making movies. So, along came Oceans’ ll.

When the call from Jack Warner for a Sinatra-Warner Pictures deal.

Rudin thought of that deal, and more. Reprise was in a deep hole, 120 albums out, and no hits.

Rudin Handles the “Next Deal”

Rudin drove over to WarnerLand and met with The Chief. A deal could be made, and Rudin was a deal-maker of skill. He liked the scuttlebutt that he (and Frank) were deep in with the Mafia. Rudin would never deny it.

He smoked big Cuban cigars. He traded getting the soundtrack to Can-Can for a non-exclusive contract with Capitol. Sinatra got semi-free with that one, but Sinatra wanted his own label.

Mickey Rudin made pages of notes. He brought extra cigars with him to Warner’s office. “You mind?” Mickey asked Jack as he lit up his next Cuban.

Negotiating the picture deal with Warner went back-and-forth quickly. But Rudin had a list that piled clause upon clause into the final deal: like Sinatra would get named Assistant to the President of the Studio. Like Sinatra would sell his own record label to Warner Bros. for 350,000 shares of WB stock, and get half ownership of the combined labels. No? Well, how about 33% ownership? Actually, about records, Warner didn’t care, one way or the other. “Well, ok.”

Rudin kept checking through his lists. Jack was late for lunch.

To Warner, this was a picture deal. This record label stuff was small potatoes. The deal got shook on. Rudin lit up his next Cuban. Inside, Rudin was deeply relieved that Sinatra’s Reprise label would stop being a financial drain on his client.

Only now would Jack Warner tell his new head of WB, Mike Maitland – yes the same Mike who’d left Capitol to take over WBR from its founding president, Jim Conkling – about the deal.

Hearing the news, Mike Maitland felt … well he never let on how he felt. But he knew this: in the expanded new company, Mike was President.

The deal set, Jack Warner and his staff did their parts. Herman Starr, head of the studio’s Music Publishing unit, MPHC, ranted about taking on Reprise’s load of debt (about $150,000, even with the accountant-softening that Reprise’s Murray Gitlin had smoothed over it.) Starr’s rants found no audience now, not since WBR had come up with Everlys and Newhart and PP&M.

Burbank Or Bust

Mo Ostin hated the idea. To work under the same roof with Maitland?

Mo scurried for new hits, hoping they’d calm Mickey Rudin, make him restore Reprise to a one-fer. Mo and his new A&R “kid” Jimmy Bowen were feeling hot. They’d released non-Sinatra-era hits, and some were actual hits: Jack Nitzsche’s “Lonely Surfer,” Eddie Cano’s “A Taste of Honey,” Lou Monte’s “Pepino the Italian Mouse.”

Trini Lopez made a real hit album: “Trini Lopez at PJ’s,” with a hit single, “If I Had a Hammer” (up to #3 on the charts).

Actual hits, but not enough hits. Mo, who told Rudin that he was “terribly disappointed and had no idea what would happen,” had no vote.

Even single hits didn’t stop this deal, though. Rudin had Sinatra’s ear, Dean Martin liked being within a film studio. Sinatra had grown a bit bored with the demands Reprise placed on him. And within Warner, tough exec Ben Kalmenson faced the WB Studio Board of Directors. He opened-and-closed the discussion in one paragraph:

“Before there is any discussion, I just want you to know that this is a deal that we’re going into. We’ve had good success with Frank in the past with Ocean’s 11. We feel we can make some good money out of this picture deal. As part of the deal, we’re going to acquire the record company, and, in turn, we will allow Frank to buy a one-third interest. All of this is acceptable to Jack Warner. In fact, Jack wants the deal, and I want the deal. I expect each of you to vote in favor of the deal. Are there any questions?” There were none.

Moving Day

Moving day approached quickly for Reprise. Deal signing on September 3; move Reprise into the old WBR building on September 25. At Reprise, three weeks to unload a hunk of personnel, pack up your desks and stuff, and head over the hill from Hollywood to Burbank.

With that, Frank and Dean and Reprise were a team with Jack now.

Frank, Jack, and Dean

On September 25, Reprise’s employees-to-continue were scheduled to drive out to Burbank, along with a van-ful of their desks, files, and baby pictures.

In the downstairs lobby at WBR, there was no welcoming party. Mo Ostin arrived first, looking “where,” and hardly assured by the sudden emptiness he felt. The van was behind sched. Behind Mo, through the day, came Mo’s secretary Thelma, Reprise’s A&R staff of two, Jimmy Bowen and Sonny Burke, CPA Murray Gitlin, a few others. But not a living label. As secretary Thelma Walker later put it, “Warner Bros. had a national promotion manager, Joe Smith. And they had a national sales manager, Bob Summers. And they had and they had and they had.”

And upstairs, Mo knew, they had a president, Mike Maitland, down at the west end of the hall. Mo’s office was at the other end, the east end. He climbed upstairs to it. The van of stuff from old Reprise was late to arrive. Mo stood in his dark-ish office, looked out the window at a cow-size air conditioner hrrumming. He just stood there, hands in his pockets.

Soon, Mo’s office got a call. Thelma yelled to him, “Mike Maitland wants to see you, Mo.”

-- Stay Tuned