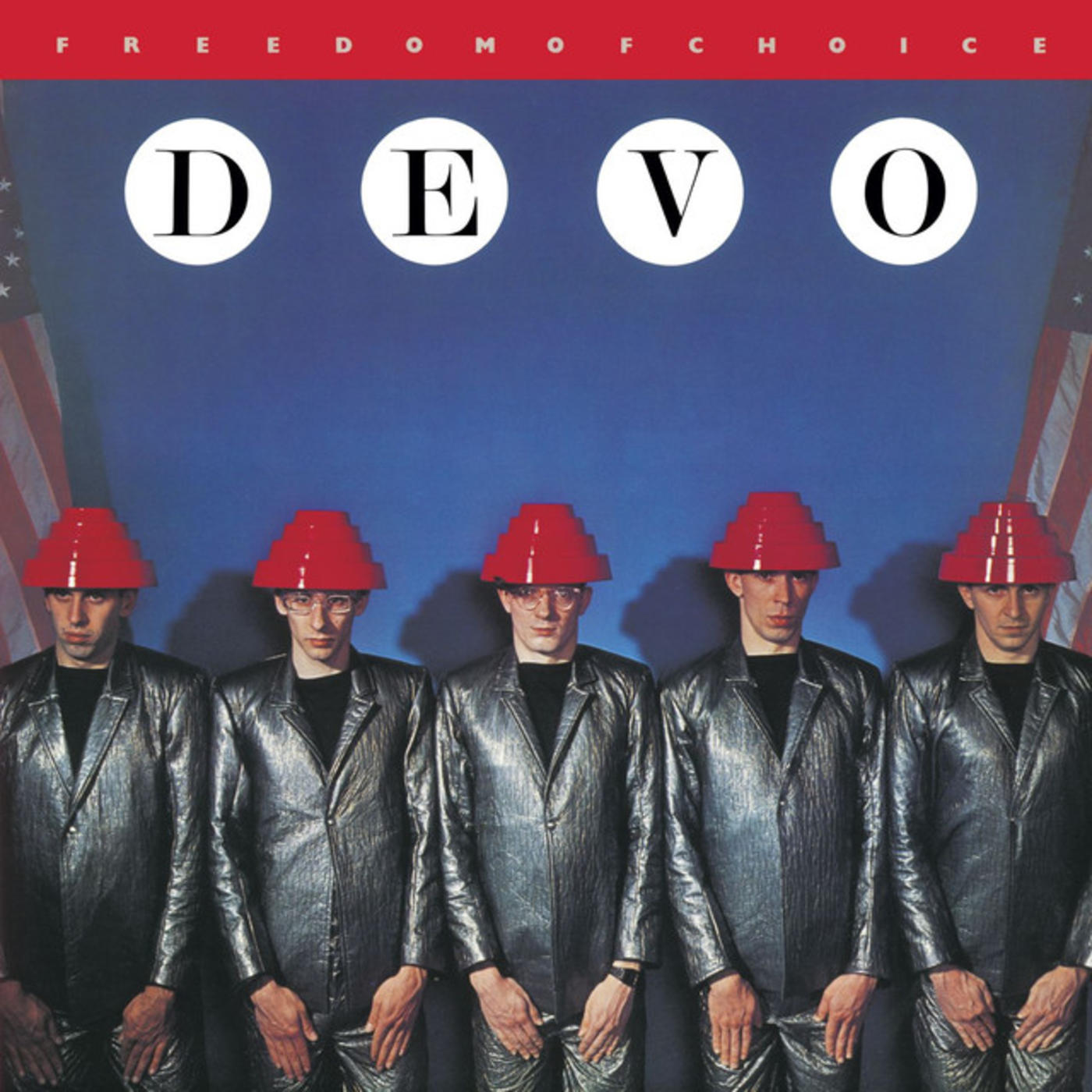

Interview: Gerald Casale of Devo

By Will Harris

This year marks the 35th anniversary of Devo's Freedom of Choice, which remains the most successful studio album in the band's back catalog and - not coincidentally - is also the seminal effort which provided the world with “Whip It.”In celebration of this momentous anniversary, Devo founding member Gerald Casale hopped on the phone with Rhino to reflect on the origins of the album, the slightly belated but nonetheless exciting success of “Whip It,” and why he wouldn't have minded if Devo had ended up being “the thinking man's KISS.”

Rhino: When Freedom of Choice came out, it was on the heels of Duty Now from the Future, and it definitely had a more mainstream feel, at least comparatively speaking. Was that intentional, or was that just the direction in which the songs were going?

Gerald Casale: Yeah, it's just how the songs were going. The first two records were really culled from material we had written - over 50 or 60 songs - between 1974 and 1977, and we had worked out, “Okay, album one will be this, and then album two will be this.” And somewhere in the recording of album two, Mark (Mothersbaugh) started to want to throw out things that we had slated to be on album two and put on some new stuff that was kind of… Well, you know, it was kind of still incubating and probably wasn't really ready. And that album was ill-received. So we decided at that point, “Well, let's write all new material and start now.” Like, “Forget about the past. Give the past a slip.”

So that record really represents a concentrated period of original writing, where we lived in L.A. for the first time and wrote all the songs in L.A., in a rehearsal space in Hollywood which was a dingy little converted neighborhood store. It still had a storefront on it, but they had taken these buildings in an area that was no longer a commercial area and rented them out as rehearsal spaces. So we'd go there every day, and Freedom of Choice was the result of what we wrote. It really was driven by this talk of love for R&B music, which Bob Mothersbaugh and I had a great love for, and we thought, “What if Devo used R&B for an inspiration, a jumping-off point?” And believe it or not, that's what you're hearing. That's how warped it got. [Laughs.] Nobody would ever listen to that record and go, “Oh, yeah, that's R&B!”

But knowing that, the decision to have Robert Margouleff produce the album suddenly makes a lot more sense.

Right! Because we really loved Stevie Wonder's “In the City,” and we loved Moog bass sounds, so those were two basic decisions: that I would play a Moog bass and not a bass guitar, and that we would use beats that were more R&B-oriented. And it's still funky robot R&B, you know. [Laughs.] Devo: from the waist up, we're Kraftwerk, and from the waist down, we're James Brown. But the waist-up part has the brain in it, so you're letting the brain rotate the hips.

When you first met with Robert Margouleff, did you have to sell him on the band's love of R&B? Given what people knew of Devo up to that point, I can only imagine that he might've been going, “Ooooooookay…”

Yeah, he was like that. [Laughs.] He was, like, “Really. Okay…” But we said, “Yeah, we're using the Moog bass. Here, listen to some of these demos!” And that sold him.

Did you guys end up working together relatively well once you realized you were on the same page?

Yeah, it did go relatively well, because he really paid attention to the bottom end, to the relationship between the bass and the drums, in a way that I totally appreciated. Because to me, any of the great songs in the history of rock 'n' roll and pop music had a really, really powerful foundation of bass and drums that were compelling and original and exciting.

In the process of writing the album, how did you come to structure it the way it ended up structuring it? Were you setting material aside either because it sounded too much like the band's earlier sound or just because it didn't seem to match up with everything else?

Well, you know, I think what was great about that process was that it represented this perfect juncture of who Devo was and who Devo were going to become, and it was the best of both worlds rather than the worst of both worlds. The writing process was open and democratic and creative. The cliché about being on the same page was absolutely true. And then there's this intersection with that point and time in the culture where everything comes together, and...we just didn't want anything on the record that we didn't like.

And there really was a “we,” so it was easy to know, “Oh, these are the songs we really all like,” because those are the ones that you'd develop, and those were the ones that you'd play over and over and get new ideas about little minutiae that musicians get interested in when they like a song, and they finally go, “Well, let's put a fill there, and why don't you do this on the bass right there?” All those silly little things that are finessing a song, you don't even bother getting into those if you aren't excited about it. So all that happened, and the record represents the songs we wrote that we liked the best that we all wanted on the record.

We also didn't have a big preference about “this is the hit” or “this is the one,” because we didn't put anything on the record that we didn't like. Frankly, all the people in our immediate peer group and then all the people at the record company immediately jumped on “Girl U Want” and said, “That's it!” And our attitude was more or less, “Okay, if you think that's it, we like that song.” And they went with that. And it went nowhere. [Laughs.]

Watch "Girl U Want" HERE

I wanted them to put out “Freedom of Choice,” the title cut, because I really liked that song and I thought it had enough of a mainstream rock kind of energy to it that maybe it had a chance. But Warners wasn't treating Devo like they would treat a mainstream hit act, and they weren't treating us to independent promotion money. They weren't out there going to Joey's Grill asking, “What do you think about this?” They were maybe meekly playing it for a couple of radio people they knew, and the radio people were kind of left over from the early '70s, all wearing satin baseball jackets, mustaches, and long hair, and they hated Devo, and they didn't like “Freedom of Choice.”

Watch "Freedom Of Choice" HERE

So that seemed like it was going to be the end of this record. It just seemed like it was over. We were very crestfallen, but we were still scheduled to go out on tour, which we did. We loved the songs, and there was still a big following for Devo from those first two records. And then - a story that everybody knows by now - there was this guy named Kal Rudman down in Florida who was a regional record promoter back before the days of conglomeration and corporate control, when regional things could happen, and he decided he loved “Whip It.” So he put out this tip sheet in the southeastern United States that went out to all the DJs at these stations, and he basically said, “Play this. This is it.” And they started playing it down there. Our management started getting reports and couldn't believe it. And then they found out that it was really peaking in gay discos. [Laughs.] And when it made it to New York City, that blew the whole thing wide open.

So Kal Rudman really lit the fire, and then it jumped to New York, and then from there, of course, it went national. We actually had to take a pause in the middle of the tour, and they had to rebook venues in the cities we were scheduled to perform in, because now the venues that we'd been booked in previously were way too small. So it just blew up suddenly, and there we were: instead of playing to 400 people, we were playing to four or five thousand people.

Watch "Whip It" HERE

As far as the origins of “Whip It,” first I heard it was a tongue-in-cheek anthem for Jimmy Carter, then I heard that it was inspired by The Power of Positive Thinking, but then I also heard that it was inspired by Gravity's Rainbow. Is it any or all of the above?

It's the third. I was reading Gravity's Rainbow, and I wrote the lyrics in one night after who knows how many pages. Because that's a lot of pages. [Laughs.] But it was because I was just so turned on by (Thomas) Pynchon's parodies of limericks and the Horatio Alger story and “you're number one,” “there's nobody else like you,” and “you can do it.” I was just kind of doing my take on it. And, of course, I was also aware of the double or triple entendre. But it worked!

The music was pieced together from four different demo tapes. Mark had done some stuff in his bedroom, and what became the bridge was this very beautiful, slow, almost classical music sounding thing with no drums on it. And then on another tape, he had the [Vocally imitates the riff immediately before the words, “Crack that whip!”] that he played on a guitar line with a drum machine. And then a drummer that drummed with Captain Beefheart had been jamming in our studio, and Mark taped him doing drum beats, just pure drum beats, and that drum beat that became “Whip It” was pretty much the way it was. Alan (Myers) perfected it, but it was this beat that this guy had done, and it was amazing. And then a fourth thing came from something I'd been doing with Mark in a live jam in the studio.

So we had these pieces of music, and I took them all and put them over that beat so that it was one time signature and now one form of instrumentation rather than all these little pieces, and…that was that! The lyrics fit so well, I didn't even have to change them, not even the meter. It was one of those things that just came together very nicely.

So was the riff really just a tweaked version of Roy Orbison's “Oh, Pretty Woman”?

Oh, yeah. [Laughs.]

Obviously, it sounds like it, but…

Oh, yeah, because I said, “Wow, when did you do that, Mark?” And he said, “Oh, I've had that for about three or four months.” I said, “Really?” He said, “Yeah, it's just 'Pretty Woman' cut in half, with two extra beats in between.” [Laughs.] And I never would've recognized it, but once he said it, I was, like, “Oh, yeah!” You take out those beats, and you can't miss it, but putting them in was brilliant. And it was a perfect example of Devo warping and mutating and deconstructing from the existing lexicon of rock and R&B.

The band eventually did a ton of TV appearances to support the album, including Fridays.

Oh, God, we were on Fridays three different times, I think. [Laughs.] They loved us. And we loved being on that show. They really let us do the kind of production we wanted and let us do all these extras, so whenever we appeared on there, each time was like doing a real show. The way we looked, the sets and everything, were always different. They even involved us in a couple of the comedy sketches. And we got to see Andy Kaufman!

And then on the flip side of things, you also got to do The Merv Griffin Show.

Well, sure. [Laughs.] That was sublime. That's another kind of Devo. That's low Devo. But to get Merv to put on the hat? I mean, c'mon: that was a triumphant moment.

Were you surprised about the controversy when you ended up missing out on a gig on The Midnight Special because of the “Whip It” video?

Um, remind me what happened? Because we had been on The Midnight Special in '79 and did five songs. It was this whole thing, and it was actually an incredible night. They used to let bands basically do a mini-set. (David) Bowie had come on there and done five songs from Diamond Dogs, with all the production and everything. So…

Well, it may be apocryphal, but I'm referring to an incident with Lily Tomlin, where she apparently deemed the video offensive to women and in turn opted out of having you on the show.

Oh, sure, and that's true. But I thought she had booted us off of her show.

Well, I've seen it written both ways, but she did host an episode of The Midnight Special in '81, so I think that's what it was.

Okay, that may be true, then. I just thought that it was her show. But whatever show it was, originally they wanted us on, but then somebody showed her the video, and she said, “Get rid of those guys! They can't be on the show!” [Laughs.] I guess she didn't see the ridiculous humor in the video. All she saw was that the lead singer was whipping a woman's clothes off…and that was that! So, yeah, that did happen. No matter what show it was, she was responsible for that.

You mentioned that you'd had hopes for “Freedom of Choice” being a hit, but it unfortunately was not.

It was never even released as a single! They never even tried it.

Oh, really? I thought it had been but just didn't do very well.

I don't think so. I mean, you have to remember that “Whip It,” when Kal Rudman got the song some heat, it was, like, September 1980, and the kids were just coming back to school and we were out on tour, so by the time America was into “Whip It,” it was January 1981. We were in the studio starting the next record, and Warners felt like they hadn't milked “Whip It” to the end yet, and they didn't feel like putting out something else because “Whip It” was still getting them what they wanted, so they felt like it would just be better if we came back with a new record off the energy and success of “Whip It.” So that was the feeling on the momentum. I've often said that it was too bad that Axl Rose never covered “Freedom of Choice.” [Laughs.] He really could've sold those lyrics. [Breaks into a surprisingly spot-on impression of Axl Rose singing “Freedom of Choice.”] That would've been great.

So when you look back at Freedom of Choice now, how do you feel that it's held up? It's iconic, certainly, but do you think it's held up well sonically?

Yeah! I mean, just personally, I think it's still the best Devo record. I love it. I'm so unhappy with the production sound of so many of our other records, where I go, “God, if this had just been recorded in a mainstream, powerful way, we would've been so much better off!” But when I listen to the odd dryness of Freedom of Choice, what I like is that it's achieved a kind of timelessness, because you can't put your finger on, “Oh, yeah, that was the sound in 1980-whatever,” like you can with so many '80s things that have the signature digital delay, echoed drum sounds, and the syrupy synths playing string lines, and those over-gated vocals… [Laughs.] But just the dryness and honesty of the production that Margouleff did with us makes this thing more timeless to me.

I'm a fan of pretty much every album Devo's done in some capacity or other, but Freedom of Choice is the one that seems to work best as a cohesive whole.

Exactly! It was a great coming-together of us as a band, creatively moving forward, and of that point in time in the culture, before it took a right-wing swing and Reagan came in. At the time, there hadn't been a real clampdown from radio, so there really was something new in new wave. [Laughs.] And punk was still lurking, and…there was just a great freedom and diversity, people were having a great time, and…there was a lot of hope.

Is there an underrated track on the album that you feel like more people should be aware of?

Well, I feel like “Freedom of Choice” is an underrated track! [Laughs.] But I don't know what else is underrated. There's some wacky tracks on there. Like “That's Pep,” which has nothing to do with rock music! We always had to have something that had nothing to do with rock music. Like on Duty Now for the Future, we had “Triumph of the Will” and “The Corporate Anthem.” We always managed to do that. But also “Planet Earth,” I love that song, but nobody ever even ran that up the flagpole.

I'm curious about the origins of “Gates of Steel,” because it's one of the few co-writes in the Devo catalog between members of the band and folks outside of the band.

Yeah, actually, after we came back from recording the first record in Germany, we were in Akron because there was this legal battle between Warners and Virgin over who had what territories for the first record, and we were suddenly just cooling our heels. Mark got together with Debbie Smith and Sue Schmidt, who were members of this girl group, Chi-Pig, that we were all friends with. I had dated Sue and Mark had dated Debbie. [Laughs.] And they had a little recording room in…I think it was in Debbie's parents' house. Or maybe her brother's house. I can't remember now. All I know is that Mark recorded a version of what became “Gates of Steel” - the music only - with them, and it was much slower and trying to be melodic and sweet. I didn't even know he did that, and he didn't mention it, but then when we were going through tapes a year and a half later, I hear that, and I loved the progression. So we started playing it together during the rehearsals for the Freedom of Choice record, and we inevitably energized it and really honed it. I had written those lyrics just as lyrics, independent of any song, and we would share notebooks and sketchbooks and lyric books and have them in the studio for anybody to look at, so when Mark liked those lyrics, I said, “Well, let's try them on that music!” And it was just perfect.

The song “Cold War” was a collaboration between you and Bob Mothersbaugh. You and he certainly worked together here and there, but not as much as you and Mark. Was it just a case where once in awhile you and Bob would just sit down and see what shook out?

Yeah, we actually collaborated a lot. It's just that a lot of the things we collaborated on never made it onto a record. In the early days, I shared a house in Akron with Bob - we co-rented it - and that's where all the rehearsals took place, so Bob and I would play a lot together when Mark wasn't around, because it wasn't like a daily thing where he'd show up. That was in, like, '74, '75. Bob and I wrote a lot of things, and then that kind of just… You're right, it just kind of subsided into the background. But during the writing of the Freedom of Choice record, we'd find ourselves there odd hours. [Laughs.] We were working long hours, because when you're excited, you don't go, “Oh, it's five o'clock, time to go home.” It wasn't like that. So Bob and I would be there on a number of nights, just with a PF 4-track and us, and we did that one night. I think it was in, like, November of '79.

So when Freedom of Choice broke big, did you think in terms of, “At last: we're finally bringing Devolution to the masses”?

Well, yeah! That was always my vision and dream. When we were raked across the coals critically by Alan Jones from Melody Maker in England, he said that we were - and this was his big putdown - “the thinking man's KISS.” [Laughs.] And I thought, “You know what, you asshole? That's not a bad thing!” Because just imagine if we could be as popular as KISS and as iconic as KISS and yet have this message that Devo brings rather than this silly, tired message of parties, drugs, and getting the girl. What if Devo could have as big an audience as KISS but with this alternative message? That would be a true breakthrough. True subversion. [Sighs.] But it didn't happen.

Well, for one brief but bright moment, it did.

Yeah. I guess before the powers that be said, “You know, those guys don't really play ball, and they're not really mainstream, and we've started paying attention to their lyrics and we don't really like what they're trying to tell kids. They're telling them to think. That's not good.” [Laughs.] I remember going out on promotional interview tours for New Traditionalists, and we were talking about how, “Hey, it's time for new traditions! You've got to quit believing all of this fundamentalist type of stuff!” And Reagan had kind of empowered the religious right, and they were hugely back in the spotlight and influential with all that kind of fundamentalist, cram-the-morality-down-your-throat Christianity, and we were really getting attacked. You know, “Are you saying that you don't believe in God? Are you saying that morality doesn't matter?” All this stuff. It was, like, “No, we aren't saying any of that.” But we were getting really attacked, and we just had a bad feeling about it all.

Yeah, maybe Devo was never destined to be a completely mainstream band.

[Laughs.] In hindsight, I guess you can't argue with that. But at the time, I was fighting the good fight and trying very hard to maintain our aesthetics and be successful. After all, that intersection, that combination, is the most interesting thing, isn't it? It's easy to be an obscure, artsy weirdo band, and it's easy to be a meaningless baloney mainstream band putting out pap, but it's very hard to be Bob Dylan or the Beatles or David Bowie, where you get the whole enchilada. And at that moment, with Freedom of Choice, we really had it going.