Jazz Appreciation Month - "String Theory"

Stringed instruments have a place of honor among the jazz ensemble along with horns and keyboards. To mark Jazz Appreciation Month, we salute all the virtuosos for whom the string's the thing.

Perhaps the most appropriate person to lead the parade is Eddie Lang, considered by many to be “The Father of Jazz Guitar.” His own father was an instrument maker, and Lang studied violin as a child before mastering the guitar. He was a fixture of the New York music scene of the late 1920s, performing with the likes of Hoagy Carmichael, Bing Crosby, and Joe Venuti, an old school friend. Venuti can be called the father of jazz violin playing, and his duets with Eddie Lang for Okeh are among the true gems of early jazz.

Lang's death at age 30 cut the partnership short, but not before it could inspire a couple of other string players across the ocean. Jean “Django” Reinhardt learned the banjo and guitar while growing up in gypsy caravans in France. At one of these encampments, he was badly burned in a fire, leaving a couple digits of his left hand paralyzed; Reinhardt adapted his playing style so that he could solo with just two fingers. Shortly thereafter, Django discovered jazz and became one of its leading exponents in Europe. Like Eddie Lang, he teamed with a talented violinist, Stéphane Grappelli, and their Hot Club de France recordings are jazz milestones.

Acoustic guitars had a tough time competing with the brass sections of larger orchestras, but with the development of electric amplification, the six-string found its voice in the big bands. Charlie Christian was a guitar prodigy when producer John Hammond recommended him to Benny Goodman; he quickly became one of the bandleader's most popular soloists. Seeking to emulate the tone of a tenor saxophone, Christian's work wound up influencing a host of bebop horn players as well as nearly every electric guitar player of note.

Before leaving the big band era, we should tip our Stetson hat to the King of Western Swing, Bob Wills. Though found most often in the country section of your music retailer, he and his Texas Playboys drew many of their arrangements from jazz. Wills was an accomplished fiddler, and his band showcased such top instrumentalists as steel guitarists Leon McAuliffe and Herb Remington, and mandolinist Tiny Moore.

Perhaps the first great guitarist of the post-WWII jazz scene was Wes Montgomery. A disciple of Charlie Christian, Montgomery performed in Lionel Hampton's band for a few years before setting out on his own in the late 1950s, recording for Riverside and later Verve. Wes played with his thumb rather than a pick, and his innovative use of octaves and block chords in his solos added to his distinctive style.

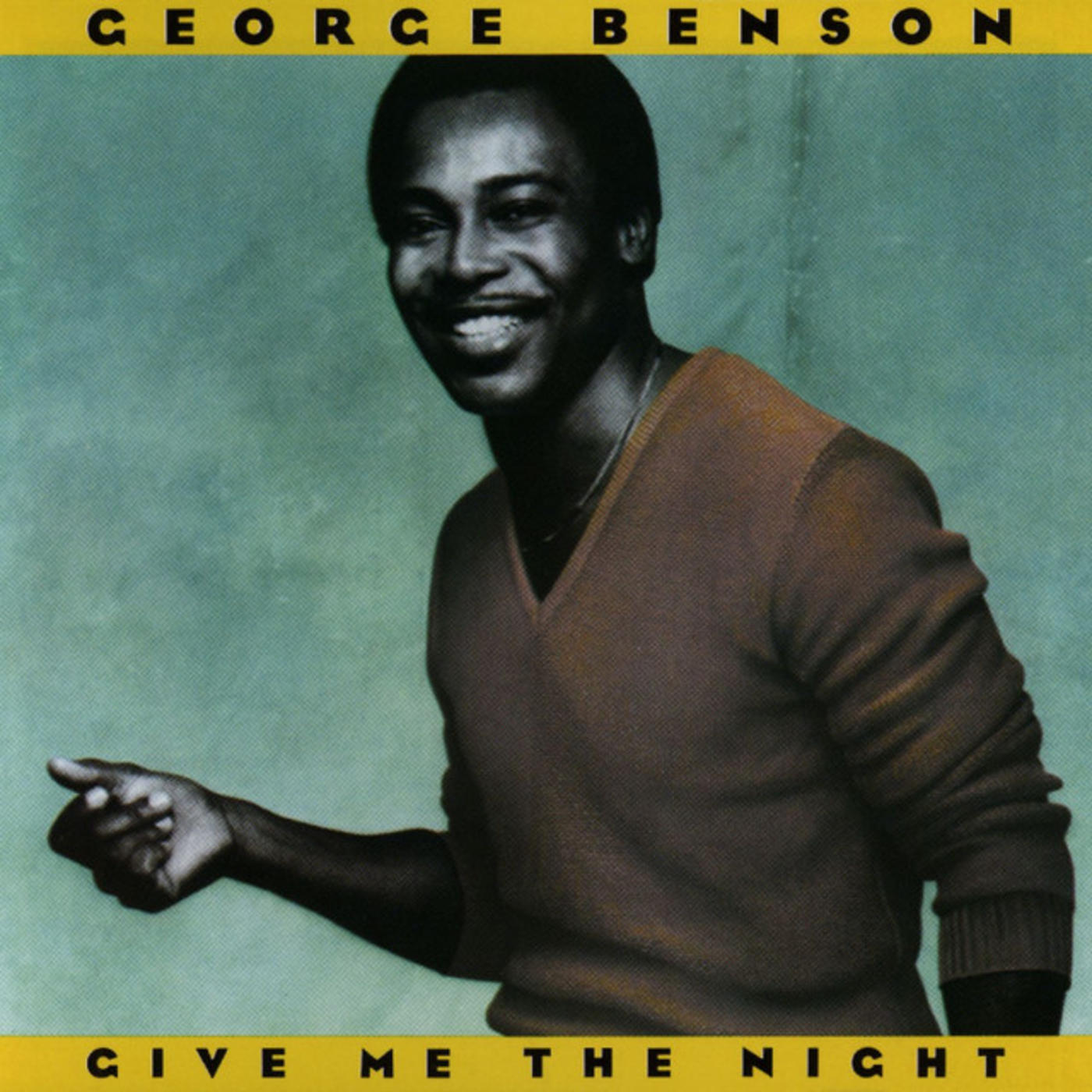

Among Montgomery's fans was George Benson, who cut his first album the year The Beatles hit (he would later devote an entire album to Abbey Road covers). Benson's career in the 1960s included memorable guitar work with the likes of Jack McDuff and, inevitably, Miles Davis, but it was not until his mid-1970s recordings for Warner Bros. that Benson became a major star. With George on lead vocals, “This Masquerade” became a Top Ten hit and earned a Grammy Award (one of ten for the singer-guitarist). George Benson remains one of the most successful performers at the nexus of jazz, R&B and pop.

Fusion was all about incorporating rock and other musical colors to the jazz palette, and like rock has produced a handful of guitar heroes. British-born John McLaughlin played on some of Miles Davis' greatest fusion albums (Bitches Brew even includes a song named after the string-bender) before forming the Mahavishnu Orchestra, which blended jazz and Indian styles. Echoes of fusion can still be heard in the smooth jazz and new age sounds of 20-time Grammy winner Pat Metheny.

Fusion also gave us a genuinely great violinist in Jean-Luc Ponty. Classically trained but intrigued by the possibilities of the electric violin, Ponty's bravura playing brought him legions of admirers in the jazz community and even a few (like Frank Zappa and Elton John) in the rock world. Signing with Atlantic in the mid-1970s, Jean-Luc Ponty released a string of Billboard Top 5 jazz albums; he continues to push musical boundaries as a performing and recording artist.

The bass is often relegated to the back of the jazz band, but it may have played an even bigger role in the music than the guitar or the violin (at least in terms of the standup bass, it certainly boasts a bigger stage presence). Rock listeners may be trained to focus on the instrument's rhythmic pulse, but in jazz, the bass frequently carries the melody. Charles Mingus took full advantage of this, his unconventional work as a composer and instrumentalist drawing freely from avant-garde, bebop, classical and gospel traditions. Such '50s albums as Pithecanthropus Erectus, The Clown, and Mingus Ah Um show why his reputation as a genius is well-earned.

Jaco Pastorius was as spectacularly talented on the electric bass as Mingus was on the acoustic. Starting out in Florida in local pop-rock combos, Pastorius was eventually drawn to jazz, and by the mid-1970s had won a spot with fusion leaders Weather Report. His exceptional fretless bass work with that group turned Jaco into an in-demand session musician and, by the early 1980s, a solo artist and bandleader whose intuitive playing could move effortlessly from funk grooves to lyrical solos.

Jaco's star burned brightly but briefly (he died at 35), but such bass heroes as Ron Carter, Stanley Clarke, Charlie Haden – and guitar greats like Al Di Meola, Stanley Jordan and Lee Ritenour – are still out there, strumming, plucking and bowing away. The “string section” remains one of the most potent forces in jazz.