Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Atlantic Grows Albums

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

It is now 1960 and, like the rest of the record business, Atlantic Records -- now 12 years old – is changing from a “singles-hits” label. Time for adulthood? Atlantic had grown up with 45 rpm records that spun around like little donuts. But now, records had grown wider, and revolved slower (33 rpm).

But those 33 rpms but sold more songs per disc. For more money.

One bonanza that came to labels with LPs was “compilations” -- LPs that reached back into vast catalogues of old singles, now to be assembled (compiled) and often get re-labeled as a “Best Of” or “Greatest Hits Of.”

But also, Atlantic – like most all labels – when signing a new artist contract now, saying “yes” now meant recording 12 tracks, not just two or four. That meant a bigger need for more “hit-possible” songs per artist. Especially in Atlantic’s métier – the rhythm and blues market – this hunger for hits created its own revolution.

We’ll start this five-year product switch with an Atlantic veteran, Ben E. King, in 1960.

Ben E. King

King had been one the main voice of The Drifters in 1958, singing the lead in about 12 Drifters’ hits: “There Goes My Baby,” “Save the Last Dance for Me,” “This Magic Moment,” and “I Count the Tears.”

But when King asked the Drifters’ boss and owner, George Treadwell, for more money, Treadwell just bade King “goodbye.”

Treadwell owned the group’s name, and ran the group like is was his kennel.

So in May 1960, King went solo and started performing as Ben E. King. Atlantic went along with him, and signed Ben E. to its Atco label.

Soon enough, in 1961, out came a hit ballad in Ben E.’s own new name: “Spanish Harlem.” (Words by Jerry Leiber; melody by feisty young Phil Spector, who’d now made his home at Atlantic, even sleeping in the office there).

There is a rose in Spanish Harlem

A red rose up in Spanish Harlem

With eyes as black as coal that look down in my soul

And starts a fire there and then I lose control

I have to beg your pardon

I'm going to pick that rose and watch her as she grows in my garden

I'm going to pick that rose and watch her as she grows in my garden

And then Ben E. on Atco came out with “Stand by Me” (by Leiber & Stoller).

When the night has come and the land is dark

And the moon is the only light we'll see

No, I won't be afraid, oh, I won't be afraid

Just as long as you stand, stand by me

So darling, darling, stand by me, oh, stand by me Oh, stand, stand by me, stand by me

Ben E. King’s records for Atco kept his baritone voice a frequent visitor to the Top 100 Billboard charts through 1964. Then, with the invasion of British pop, R&B would fade more into the background, at Atlantic and ‘most everywhere.

Evaluating Ben E. King’s career at Atlantic/Atco, Ahmet Ertegun put it this way: “King is one of the greatest singers in the history of rock and roll and rhythm and blues.”

But in the early ‘60s, Atlantic had little album star power. What, for Atlantic’s founders – Ahmet, Wexler, & Co. – had once been a super hobby – R&B hit singles -- now felt like a shack in need of home repair.

Inside Atlantic: 1962

In 1962, Atlantic hired a “financial guy”: the tall and bright Sheldon Vogel, CPA. His memory of that era differs from the hyped-up memoirs created by its “star executives.” He puts Vogel’s recollections simply:

“I started in 1962. Atlantic was basically run by Miriam Bienstock. Ahmet was never seen. I mailed him a check every month for $2000. The company had lost money for several years.

“The principal owner was Dr. Vahdi Sabit, also never seen. Miriam kept track of all the record quantities on index cards, and she ordered production based on the cards. She and Jerry (Wexler) fought all the time. Jerry was the poorest of the group, and was always anxious to sell.”

(Vogel stayed with Atlantic for decades, and is still around with a wife and 22 pet lap dogs in their home in New Jersey.)

Given the scarcity of Ahmet Ertegun, most A&R decisions at Atlantic had fallen to Jerry Wexler, who had pled allegiance to Rhythm & Blues. Not pop. Atlantic remained centered on making black hit singles. Simple: Just a hot song paired with a hot voice.

Artists Need Repertoire

Sometimes Atlantic’s thirst for hit songs for its artists caused fights. Like when Wexler got a demo of Wilson Pickett singing nine of his newly-written tunes, one of which caught Wexler’s thirst for a hit.

Wexler rushed into the studio recording one of those nine -- “If You Need Me” -- for Atlantic’s own Solomon Burke’s next single. It was a slow-burning ballad, with a spoken sermon in it.

If you want me, send for me

I said if you want me, want, all ya gotta do is send for me

Don't wait too lo-o-ong, just-a pick up your phone

And I-I-I'll (hurry home where I belong)

People always said, darlin', that I didn't mean you no good.

And you would need me someday.

Way deep down in my heart I know I've done the best I could.

That's why I know that one of these days, it won't be long,

you'll come walkin' through that same door (I'll hurry home)…

Wait! When Wilson Pickett sent in those songs, he had expected “If You Need Me” to be his own first single, sung by him as a new Atlantic artist. All by himself.

Wexler cut “If You Need Me” as Solomon Burke’s single, while Wilson Pickett, crazy mad at this, rushed his version out via little Double L Records, distributed by Liberty. The battle of the singles was on.

Wexler threw his all into winning the battle. His “all” was mighty. Calls to Atlantic’s DJ “friends,” displays in stores, whatever it took, Wex put behind the Burke version.

Result: Solomon Burke’s went up on the charts for 11 weeks, peaking at #37. Wilson Pickett’s original stumbled up the charts for just 6 weeks, peaking at #67.

And the way things work, Wexler also went after Wilson Pickett to sign with Atlantic in 1964. When they met, Wexler asked Pickett if was still angry over that Solomon Burke single, Pickett came right back and told Wex, “Fuck that. I need the bread.”

Wilson Pickett and Percy Sledge

So finding repertoire for Wilson Pickett now got added to Wexler’s addenda.

Pickett’s third attempt at a hit single on Atlantic came in 1965 after a session at Memphis’ Stax Records: “In the Midnight Hour.”

I'm gonna wait 'til the midnight hour

That's when my love comes tumbling down

I'm gonna wait, wait 'til the midnight hour

That's when my love begins to shine, just, you and I

Oh baby just, you and I

Nobody around baby, just, you and I, all right

You know what, I'm gonna hold you in my arms

Just, you and I, oh yeah in the midnight hour

Oh baby in the midnight hour

But Pickett’s temper was out of control, daily. He regularly carried a gun. He got known as “The Wicked Mr. Pickett.” He’d gotten banned from Stax Studios, after one day starting a fistfight with Percy Sledge in its studio.

In March, 1966, Sledge recorded his own first Atlantic song, “When a Man Loves a Woman.”

When a man loves a woman

Can't keep his mind on nothing else

He'll trade the world

For the good thing he's found

If she's bad he can't see it

She can do no wrong

Turn his back on his best friend

If he put her down

After Stax had slammed its door on Pickett, Wexler decided to move his Pickett sessions down to Muscle Shoals, a studio in Sheffield, Alabama.

Wexler and Pickett flew down. Their recording entrepreneur there, Rick Hall, met the plane. “Pickett was a wildcat,” he recalled. “He got off the plane in our little cotton patch of an airport, ready to go. He was wearing this hounds tooth coat, looking like he just stepped out of the pages of a fashion magazine – hair all slicked back, flashing smile, built like a running back for the New York Giants. I’m thinking to myself, How the hell am I gonna control this guy?”

Pickett carried this tough-guy attitude in his voice. He could cut through songs with authority. He used that voice on a series of Atlantic hits: “Land of 1,000 Dances,” his biggest R&B and pop hit. Then “Mustang Sally” and “Funky Broadway” and “In the Midnight Hour.”

Pickett would remain on Atlantic until 1972. He continued to out-macho any man he’d meet. He got his ways.

Ahmet Ertegun recalled that once, when Pickett was furious over the work of Atlantic’s own studio head, Tom Dowd, “Wilson Pickett walks in the room and comes up to Jerry Wexler and says,’Jerry,’ and he goes, ‘Wham! And he puts a pistol on the table. He says, ‘If that motherfucker Tom Dowd walks into where I’m recording, I’m going to shoot him. And if you walk in, I’m going to shoot you.’ ‘Oh,’ Jerry said. ‘That’s okay, Wilson.’ Then he walked out.”

In that moment, Ahmet and Wex learned a new record business phrase: “Artist Relations.”

Pickett lived on until age 64, when after a heart attack, he was buried in Reston, Virginia, presumably without his gun.

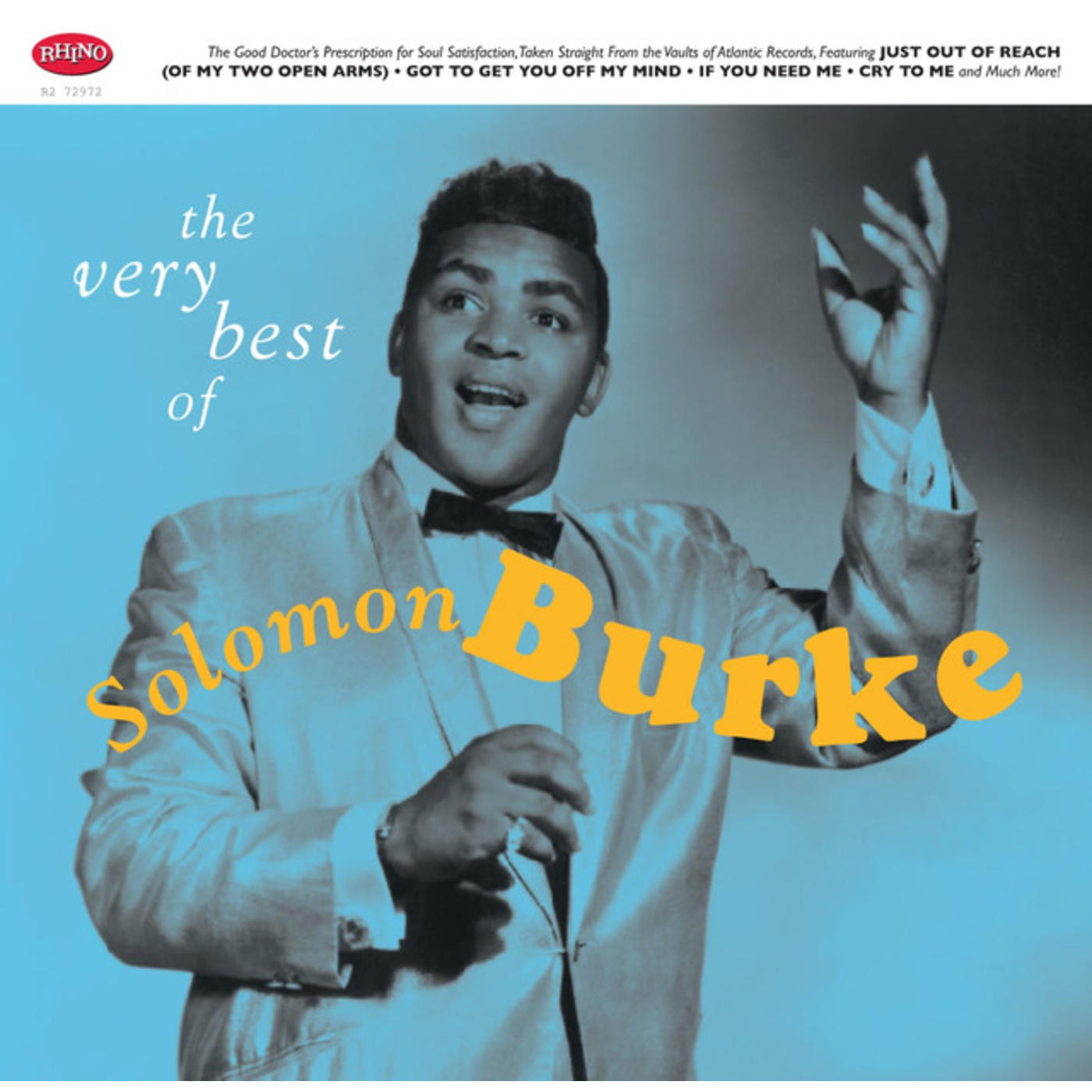

Solomon Burke

Back to where we started this trip: In November 1960, a singer named Solomon Burke came up to Jerry Wexler’s office. Wexler’s secretary buzzed in: “There’s a Solomon Burke out here. He doesn’t have an appointment, but he wants to see you.”

Atlantic, especially Ahmet, was already feeling uneasy about its artists not making long-term profits. Ray Charles had moved off to sign with ABC. Bobby Darin had moved off to Capitol out west.

And in walked Solomon Burke. Another soul singer? Yes, but one who sang beyond R&B, and had car loads of charisma.

Wexler wanted Burke signed to Atlantic. He met with what he called “a piece of work – wily, highly intelligent, a salesman of epic proportions, sly, sure-footed, a never-say-die entrepreneur.”

Within ten minutes, they’d signed a “handshake deal.”

Solomon Burke becomes a star that Atlantic could use.

Burke, however, did not fit well into Wexler’s definition of “hit single.” And Burke would not even let Atlantic call him an “R&B singer.” He considered R&B to be “the devil’s music,” and a profanity to his church. Wexler did not, of course, take this with a smile. They compromised by calling Burke “a soul singer.”

They started to make hits, and found that Burke’s “soul music” sold well, especially down South, where his style got described as “river deep country-fried butter-cream soul.” Down South, singles were still the main meal, too.

Recording with all his heart, Solomon Burke coupled gospel/soul with screaming delivery with the frenetic displays of dancing singers. Organ accompaniment and preaching style singing prevailed. His voice bore churchly authority.

Solomon Burke was later given credit by Ahmet for Atlantic staying solvent from 1961 to 1965.

Thirty-two Solomon Burke singles filled Atlantic’s R&B cash box (though none of them reached even Top 20 on the pop charts). Among them:

1961: “Just Out of Reach (Of My Two Open Arms)”

1962: “Cry to Me”

1963: “If You Need Me”

1963: “You’re Good for Me”

1964: “Everybody Needs Somebody to Love”

1965: “Got to Get You Off My Mind”

1965: “Tonight’s the Night” and a cover of Bob Dylan’s “Maggie’s Farm”

How R&B Went Inside the Heart

“I rate Solomon Burke at the very top,” Jerry Wexler said in 2003. “Since all singing is a trade-off between music and drama, he’s the master at both. His theatricality. He’s a great actor.”

Next:

In 1963, Burke agreed to being crowned the “King of Rock ‘n’ Soul.” At the ceremony dubbing him that, Baltimore DJ Rockin’ Robin presented Burke with a cape and crown that Burke thereafter always wore coming on stage. Soon, Solomon added to the trappings: beyond the cape and crown, there’d now be a scepter, robe, dancing girls, and colored lights.

Burke once employed a midget who hid under Burke’s cape when he walked onstage. When Burke threw off his cape, the hidden midget would then float it off stage left all by itself.

At his shows, Burke adopted the house-wrecking tactics of black preachers. He had folks running down the aisles to be saved by his music.

In 1969, Burke left Atlantic and moved over to Bell Records. And after Bell then on to 20 or so more labels. Asked why, he said Atlantic “just wasn’t home anymore, wasn’t family.” He complained that he’d just not “being treated properly.”

Before he left, Atlantic had made Solomon Burke an album artist, as the public now found appealing. In his first years, Atlantic began with these albums:

Solomon Burke's Greatest Hits – 1962 (Atlantic 8067)

If You Need Me – 1963 (Atlantic 8075)

Rock 'n' Soul – 1964 (Atlantic 8096)

The Best of Solomon Burke – 1965 (Atlantic 8109)

Rock and … Whatever

But by ’63, pure R&B signings were mostly over now at Atlantic. And most every other label.

Atlantic’s core strength – rhythm and blues – was no longer the central theme of the label. Signings now included Sonny and Cher, The Bee Gees, and acts from afar.

Wexler held steady to his R&B work. Dropping his black acts, even with the late-Sixties looming payola “scandal,” felt to him dangerous, because “the white acts Atlantic had that then were just ‘bubbling under’ and would never replace those R&B revenues.”

But Atlantic switched its focus from Memphis. From black soul to white bands like the Young Rascals (call it “blue eyed soul”).

There had to be a solution for Atlantic somewhere. And Ahmet was after that solution in, of all places, London.

-- Stay Tuned