Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Finding a New Audience

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

Frustration was a good word to sum up Warner-Reprise’s big, August 1967 sales convention. With the company now doing well, Warner could afford to hold this year’s Fall Product Intro in a place better than the usual bunch of big city hotel’s all-purpose “ballrooms.”

1967 felt like time to treat Warner’s indy distributors better than setting up a table on one side of the room with coffee and cinnamon rolls, and better than dealing with independent distributors whose whole idea of a smash hit is “we’ll buy six, get one free.”

1967, expectantly, Warner set its convention in one little city of delight: the town of Kauai, Hawaii, amid palms, sunshine, and rum drinks.

Distributors flew in to Hawaii from across North America, and one even from Paris. They hugged and talked chummy. Why not! Warner-Reprise had grown to be #1 in their sales. These local distribs walked under the palms, felt hip and show bizzy here, because linked to Warner/Reprise they’d sold tons of Peter, Paul & Marys and Frank Sinatras and stars like that.

Kuaui was feel-super time.

One Warner promotion man (San Francisco) walked down into the ocean, disrobed there, left his clothes underwater, then walked naked back into the hotel lobby to his room. He was greeted with cheers.

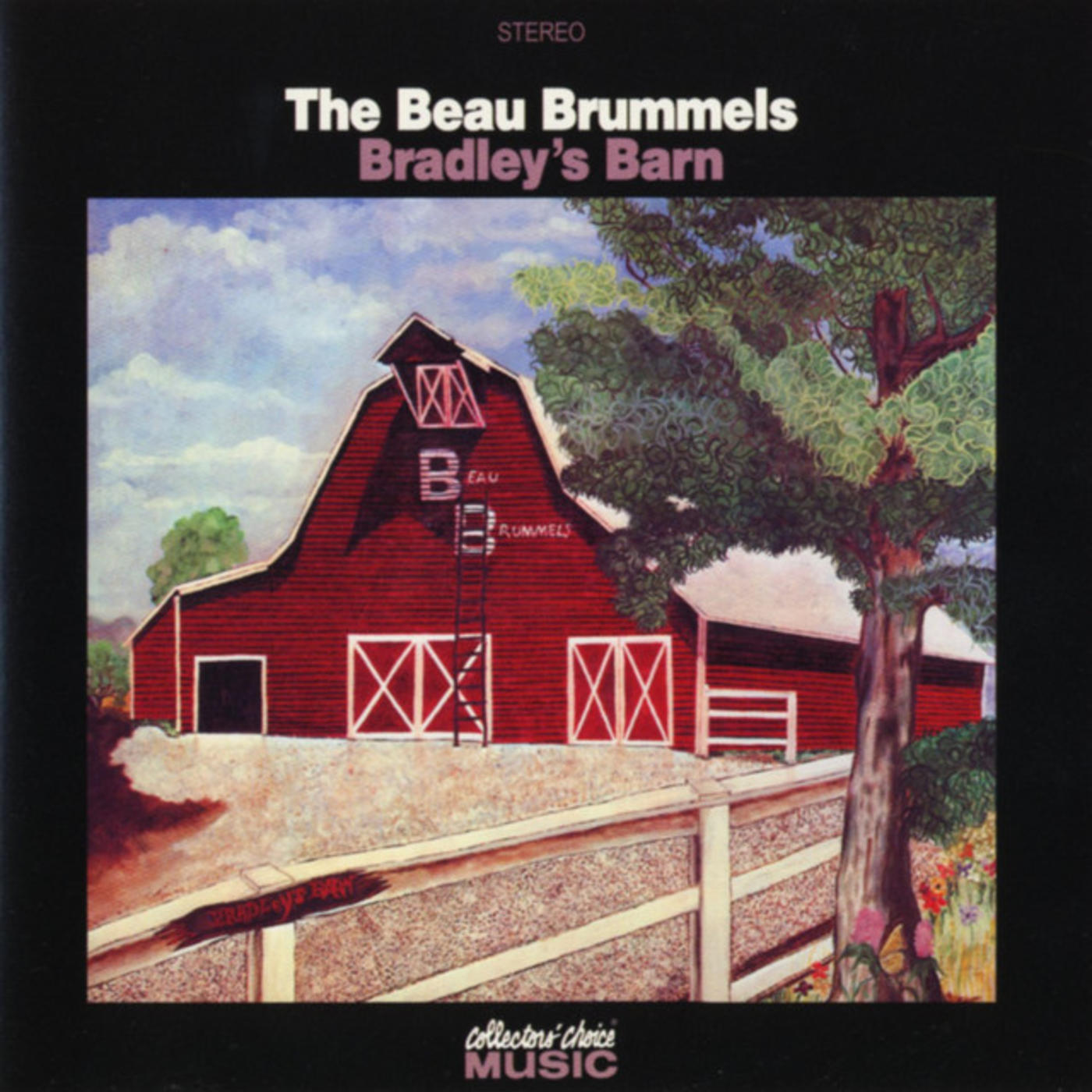

What was amiss was, back on the Mainland, distributor regard for a tiny, newer audience. A young audience that was buying newer artists – like The Kinks, The Fugs, The Beau Brummels, Frank Zappa, Arlo Guthrie, Joni Mitchell, Neil Young, and even The Electric Prunes.

Ho-hum. That’s just kids’ stuff, these distribs knew, and kids in stores means “no cash.” So those distributors, they thought Warner’s “up and coming” acts were just fugged-about-its.

How to Sell LPs to Weirdos?

Monday was “next albums” showtime.

After the Kauai slide-show demo of tracks from Jimi Hendrix’ Are You Experienced, Reprise head Mo Ostin felt the auditorium grow cold as Alaska. Mo checked the distributor buys.

Detroit ordered 175 copies, with 25 of those free. Mo felt 175 was hardly the golden pathway to profits heaven.

Not to be underdone, Charlotte’s distributor’s order for Hendrix was a grand total 6+1 (“for every six you buy you get one more free” was the convention deal). Not how to build a label these days, and Mo Ostin felt (but did not blab about) frustration. But inside, Mo Ostin knew some things had to change. And distribution was at the top of his “to change” list.

What he and Joe Smith yearned for was distribution that wanted to move forward, out to where the market was growing: to hip kids.

Within months, in 1968, and everything was changing all through America. Robert Kennedy was shot. Otis Redding, dead in a plane crash. Race riots burning Detroit. Martin Luther King Jr., shot dead. For R&B labels like Atlantic, it was as bad. Stax Records, doors closed. And for Warner, it was “frustration” – no way to get albums to buyers.

Radio, God bless it, seem to be totally ignoring Warner/Atlantic’s odder artists, hippies who get called “fringe artists.” Like Randy Newman, like the Dead.

Step One: Get Attention via Ads

Since Warner-Reprise’s traditional Marketing-exec (Joel Friedman) was going on leave for a year to study for his Law Degree exam, Mo turned to the labels’ liner notes writer and asked him to do ads. Mo just came into his office and said, “Here, you do it.”

So, until Joel Friedman would return (after about a year), many Warner ads were different. On behalf of the can’t-get-airplay, the label wrote attention-getting ads to run in what got called “the underground press.” Free newspapers for street kids, out each Friday. Cheap space for any ad, maybe $70 a page, so why not?

“What have we got to lose?” was the motto. These new ads spoke were oddly candidly. Said stuff real ads never said, with copy like “We’re really batting zero on this album.”

Ads directed at young ears that had grown weary of The Kingston Trio, Vic Damone, and Lawrence Welk. Ads that kids would remember, not just breeze past.

The ads found their audience; hip kids who lived in Haight-Ashbury and Laurel Canyon and even in Atlanta and Charlotte.

The new, fringe market ads created a buzz. That buzz was heard first by label executives, from the lips of hope-you’ll-sign-us underground artists. Such talk made Warner/Reprise feel suddenly hip with the long-haired, guitar-driven “artists” (we no longer referred to them as “singers”).

Later, Joe Smith recalled, “Out of that advertising, I think, came the whole philosophy of our company. Our advertising has been a major factor in attracting artists.”

But those ads, no matter how feel-good, still did not get records played on radio, nor sold by Warner distributors into record stores. “Underground” continued. Artists like Van Dyke Parks and Joni Mitchell felt frustrated, too.

Warner Goes Creative

When Joel Friedman returned from his year off, having flunked his bar exam, back to run marketing again at WBR, Mo Ostin stepped in and told Joel that they’d decided to keep doing advertising with the new crew.

But ads alone had not impressed the six-plus-one distribution indys Warner and Atlantic had across North America.

Cheap, hip newspaper ads had not got into the ears of the underground hippies. More needed doing, so…

In fact, WBR had decided to create a new department called “Creative Services.” So a Staff of Creatives was born. And that department would now splatter its flippancies across WBR’s Publicity and Artist Relations and Art and Editorial and Merchandising areas.

Ears to the Rescue

Up ‘til the mid-Sixties, radio promotion had been, for labels, a high-pressure business. Most radio promoters worked for local distributors, and were adept at pay-for-play, soon called Payola. Hot Top 40 stations and their DJs knew the feel of special kind of handshake with local promo guys, but Top 40 hands never got shook over artists still underground.

Fortunately, a second form of radio station was cropping up, one called FM. FM didn’t even try to fight it out ear-to-ear with AM Top 40 stations. Instead, FM slowed it all down, DJs talked relaxed, played longer cuts than the usual, three-minute singles, and accumulated rapt, hip listeners.

To get through to FM jockeys, Warner created its own “underground news press” magazines, a new one issued each week, written with the same sassy prose as its ads had come to. Fun to read.

In year one, these weeklies were named Circular, and thousands of trade copies went out each Monday, articles chatting about new artists, sounding unlike trade mags like Billboard, and even with their own ads, like:

QUALIFIED GIRLS:

Major record company now interviewing girls to be

used in a series of paternity suits to bring fame to some

of our less fortunate artists. Send scatological resume

of past experience to Box 5949, Columbus, Ohio.

Samplers

Still more came out of Creative Services. Aimed at underground record lovers, Warner also devised Sampler albums. These were not put on the market. They were double-LPs you could buy by mail for $2 tops, or even cheaper if we thought of a silly-enough deal. With no “plus shipping.” Samplers would have around 28 overlooked tracks from artists Warner/Reprise wanted heard, even this way.

They got called “Loss Leaders,”

They got fans involved. We started to advertise these “latest-greatest you’ve never heard of Loss Leaders” on regular albums’ innersleeves, there pitching them for $2 per double LP. They were a hit, and Creative Services put out two or three a year in a multi-year series with many attractions, including samplers titled “Deep Ear” (during 1974’s “Deep Throat” age) and “The Big Ball.” To write the notes, they turned to a local, oh-so-hip radio guy named Dr. Demento.

Ads for these Samplers sounded like a new Warner voice:

If you’re as suspicious of big record companies as we feel you have every right to be, we avert your qualm with the following High Truths:

This is new stuff, NOT old tracks dredged out of our Dead Dogs files. If our accounting Department were running the company, they’d charge you $9.96 for each double album. But they’re not. Yet.

We are not 100 per cent benevolent. It’s our fervent hope that you, Dear Consumer, will be encouraged to pick up more of what you hear on these specials albums at regular retail prices.

That you haven’t heard much of this material we hold obvious. Over 8000 new albums glut the market (and airwaves) each year. Some of our Best Stuff has to get overlooked. Or Underheard. Underbought. Thus, we’re trying to get right to you Phonograph Lovers, bypassing the middle man.

Each album is divinely packaged, having been designed at no little expense by our latently talented Art Department.

Such sassy approaches to marketing helped get the momentum going for thin singer-songwriters, and for amplifier-intense rock groups. If you were Led Zeppelin or The Ramones, you now felt like you could be on a label that felt like home.

What More Can We Do?

Mo Ostin still felt, down deep, that independent distributors always talked like guys on their first date, not behaving like someone you wanted to live with for the rest of your life. Joe Smith agreed fully.

Creative Services had found and intrigued the new, hip audience, but more was needed.

Mo and Joe bided their time, but deep inside, these Warner/Reprise heads knew what their marketing next needed: their own, Warner-owned distributors, ones who’d back every album, no matter how weird. No more “six-plus-one-free” guys. Our guys.

It has to happen.

-- Stay Tuned