Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Punk’s Papas -The Ramones

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

From 1974, for 22 years, up through 1996, a band whose members all adopted the same last name – RAMONE – performed 2,263 concerts, toured and toured without stop. In the first two years of this, they changed the sound of pop, especially in America. Their music was breakneck fast.Most tunes went under two minutes. Their on-stage sets lasted often about 17 minutes. They fathered Punk Rock.

Then, having fathered, they searched for a bigger audience.

It all began in high school, when in 1972 three at Forest Hills High (in Queens, NY) joined themselves into a garage band they called Sniper. They’d grown up with classic rock in their ears, bands like The Beach Boys and the Kinks.

Then one of them, Doug Colvin, changed his last name to Ramone (he explained it was like what Paul McCartney had done in his Silver Beatles days, when he called himself Paul Ramon). Then Colvin (now DeeDee Ramone) talked his classmates into taking that same last name.

The four were:

Joey, the lead singer

Johnny, the lead guitar

DeeDee, on bass, best known for his speed-shout to set the song’s tempo: “1,2,3,4!”

Tommy, the first drumming Ramone, but moved on to other jobs with the band. Replacing him in 1978 in the quartet: Marky, on drums.

(There were a few other Ramones as the decades whipped and whizzed by, but these four are enough to remember for now.)

Soon enough, after school and after fumbles, the Ramones knew that Forest Hills was not big enough. They moved to downtown Manhattan, home of two very hot spots: Max’s Kansas City and CBGB’s, where they first performed on August 16, 1974. One reviewer wrote, “They were all wearing these black leather jackets. And they counted off this song…and it was just this wall of noise. This was something new.”

In the year 1974, America was deeply felt by the Ramones. 1974 was Vietnam, it was Nixon resigning, Patty Hearst captured by the Symbionese Liberation Army, a year with so much rot in it that President Carter decided that 1974’s White House Christmas Tree would not get lit up that December.

The Ramones also reacted to the highly-produced pop music of 1970s – loud and long rock ‘n’ roll. Joey explained: “We decided to start our own group because we were bored with everything we heard … tenth-generation Led Zeppelin… Everything was long jams… We missed music like it used to be.”

The magazine Trouser Press said, “With just four chords and one manic tempo… Their genius was to recapture the short, simple aesthetic from which pop had strayed…”

What the Ramones were playing on stage, however, was not on record. Yet.

What the group needed was a Ramone named Seymour.

In Comes Seymour Ramone

Seymour Stein that is. Stein had been in the record business since he learned how to chew.

And in New York, where else? At age 13, Seymour had a job as a gofer at Billboard for its editor and its charts handler. Then he’d got a job working for Syd Nathan at King Records, who trusted no one, used his fists, and lived in of all places Cincinnati. Then he’d talent-scouted for songwriters Leiber and Stoller at George Goldner’s Red Bird Records.

Goldner worked with Morris Levy, another scoundrel in the record business, who once summed up his career by saying “Yea, though I walk through the Valley of Darkness, I shall fear no evil, for I am the meanest son of a bitch in the Valley.”

That was the record world that Seymour Stein grew up in.

Seymour was introduced to his record label co-partner Richard Gottehrer via a groupie. Stein and Gotteher scrimped to start their new label, to be called Sire. But what would Sire sell? Seymour scrounged through bins in record stores for recordings to sign, to be on Sire. Not much revenue came in.

People who dealt with Stein would say “Seymour Stein, See Less Money.”

Sire had worked London, but come the ‘70s, he concentrated in New York’s low down clubs, places without disco balls, grimy walls, and deafening amps, soothing as bikini wax.

He married another hanger-out in lower Manhattan’s rock clubs, Linda Stein. They kept developing Sire.

One day in New York, Sire Records’ talent “prowler,” Craig Leon, brought back to the Sire office a demo (“Judy Is a Punk” and “I Wanna Be Your Boyfriend”) of an unsigned band. Seymour Stein played it.

The sound on the demo’s two songs didn’t sound like “record sound.” But Seymour stayed with it. The lyrics were strange. In the song’s words, girls’ names were for boys. Berlin meant not Germany but “here” somewhere.

Jackie is a punk

Judy is a runt

They both went down to Berlin, joined the Ice Capades

And oh, I don't know why

Oh, I don't know why

Perhaps they'll die, oh yeah

Perhaps they'll die, oh yeah

Perhaps they'll die, oh yeah

Perhaps they'll die, oh yeah

Second verse, same as the first

Sung, yelled, fast as, fast as, oh yeah.

Seymour recalled his reaction to first hearing Ramones. “Their melodies were very catchy and stayed with me, dancing around in my head, and it was absolutely clear that, for better or worse, underneath it all was a pop band mentality.”

The Ramones’ average set on stage lasted about 17 minutes, beginning to end.

In January, 1976, the Ramones signed with Seymour Stein’s label Sire, based partly on added enthusiasm for the group from Seymour’s wife, Linda, who started to co-manage the group with Danny Fields. Both Seymour and Linda felt it, and it was called “Punk.” While other young bands were trying to sound pop, trying to sound like the New York Dolls, what Sire Records heard was Joey, unique, totally, yelling.

Cost of signing the Ramones was kept meager: the contract advance of $20,000 got used to pay for recording the album and buying some equipment. Little more.

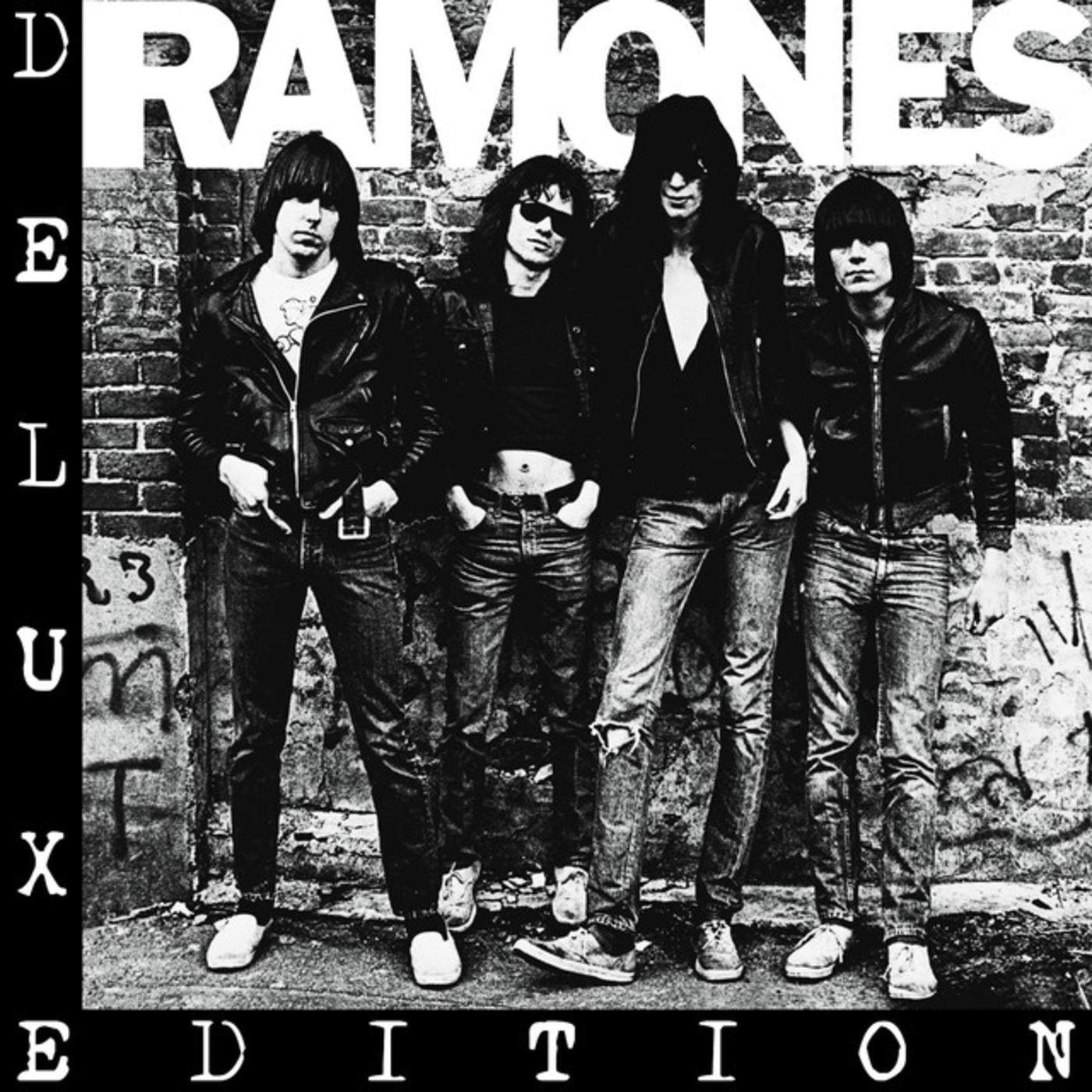

Album One

The Ramones’s first album, named Ramones, got recorded in seven days in February, 1976. The group already knew its songs; they had plenty. So: Three days to get the music laid down, then four days for the vocals. Total recording cost: $6400, a budget that was hardly Fleetwood Mac.

The album’s Track One set its style. Rock played at top speed and full volume. “Blitzkreig Bop” reached out to listeners, urging them all to start their own bands (in the song, “they” refers to the Ramones, but avoids using that “We” word):

Hey ho, let's go

Hey ho, let's go

They're forming in a straight line

They're going through a tight wind

The kids are losing their minds

The Blitzkrieg Bop

They're piling in the back seat

They're generating steam heat

Pulsating to the back beat

The Blitzkrieg Bop.

Hey ho, let's go

Shoot 'em in the back now

What they want, I don't know

They're all revved up and ready to go

The album went on sale that April. Cover just black-and-white. The band in uniform: long hair, leather jackets, torn jeans, T’s, sneakers.

Reviewers coo’d and oo’d. Robert Christgau in The Village Voice: “I love this record—love it—even though I know these boys flirt with images of brutality (Nazi especially)… For me, it blows everything else off the radio.”

And Newsday: “…the best young rock ‘n’ roll band in the known universe.”

Fans were plenty; and sales….mmm.

The album pooped. Only #111 on the Billboard chart. At the Ramone’s first big date that June in Youngstown, Ohio, ten people showed.

Maybe do better in London? At a couple of dates there, they met the Sex Pistols, also hustling a just-born punk rock scene in England.

Fans memorized their songs. Their most coveted refrain came from their song “Pinhead,” where they’d all chant “Gabba gabba hey!

Seymour’s Sire Finds Warner Bros.

Shortly after the Ramones’ first album came out, Sire’s distribution deal with ABC Records had fizzled out.

Seymour asked around. He ended up being referred to Mo Ostin, and Warner Bros. Records took over Sire’s distribution. For WBR, this was very far from a sure thing.

Mo, as often, took that chance. Because he sensed that Seymour Stein heard music and swam in it.

The Ramones now had a secure “big time” label backing them (and Sire).

Punk Quickly Peaks

“The death of punk” had by now being widely predicted, but this was only 1977. The Sex Pistols had by now toured America, and they wanted success. One critic (Ira Robbins, writing in Trouser Press) typed: “I’m not knocking rock ‘n’ roll success, but musical careers built on nihilism anti-superstardom seem a bit wobbly when the groups begin to accept the star’s life.”

Album after album sped out of Sire Records. One album even had a track that exceeded three minutes.

The Ramones got what they wanted: big, then bigger.

They adopted their own Ramones logo: Like the Presidential seal, except replace the olive branch with an apple tree branch; the eagle holding a baseball bat, not arrows; the band members’ names around the eagle. The scroll in the eagle’s beak reads “Hey ho let’s go.”

But this was not CBGB’s. And light bulbs at this year’s White House Christmas tree were now back on.

The Ramones film debut was in Roger Corman’s Rock ‘n’ Roll High School in 1979. Clearly, five years and the group had now gone Hollywood.

In 1980, out in Los Angeles, producer Phil Spector was chosen to create their End of the Century album. He slowed down some tunes. Got them a hit in England. During the recording in L.A., Spector held DeeDee Ramone at gunpoint, forcing him to play a riff rover and over and over. But Johnny Ramone knew the truth: Spector was just making a “watered-down Ramones. It’s not the real Ramones.”

Slower songs had appeal, like “Danny Says.” But … for the harder stuff, it didn’t work as well.” American Hard Core had waned. It was futile, because the Ramones got little airplay on American radio. Record companies were just not used to selling soft punk. Period.

In the next few years, the Ramones got some of their rhythm back. Speed. Short songs. But now, the band made more money selling their T-shirts than they did albums – shirts running about $19.99.

After 15-plus years, Sire and the Ramones split. The Ramones remained odd. In 1993, they recorded voices and music for animated versions of themselves in The Simpsons episode, “Rosebud.” Other bands (once counted up to 48) have since cut tribute albums of Ramones’ albums.

It was loud while it lasted. Stunning, and then … gone.

But records from those first two years, they changed pop forever.

-- Stay Tuned

Where Are They Now:

Joey Ramone, the lead singer mainly. The tall one. Born Jeffry Hyman. Died in New York of lymphoma on April 15, 2001. A street sign in N.Y., at East Second Street near CBGB’s, names the Bowery corner Joey Ramone Place. About Joey, Green Day’s Billie Joe Armstrong was heard to say, “I can firmly say that rock ‘n’ roll will not be the same without Joey Ramone. He was rock ‘n’ roll coolness… And he barely moved a finger.”

Johnny Ramone, the lead guitar. Born John Cummings. In the 1980s, Johnny stole Joey’s girlfriend Linda, whom he later married. Died of prostate cancer in Los Angeles, September 15, 2004, age 55. A cenotaph for him was built in Hollywood Forever Cemetery, near the gravesite of former bandmate Dee Dee Ramone.

DeeDee Ramone, on bass. Born Douglas Colvin. Died of a heroine overdone in August, 2002, in his home in Hollywood. His widow, Vera King, wrote her recollections of this life in Poisoned Heart.

Marky Ramone, on drums. Born Marc Bell, joining the group from 1978 to 1996. When they disbanded in ’96, he moved from band to band, with little recognition and lots of mileage still to handle.

Seymour’s Sire deal with Warner Bros. Records. Part One went on for twenty years. Good years, until 1997, then Part Two from 2003 on. It would bring riches to Burbank, including Talking Heads, Madonna, Ice-T, Depeche Mode, Echo & the Bunnymen, The Pretenders, Seal, k.d.lang, Tommy Page, Ministry, and decades more.