Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Shutting Down Reprise

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

1971

Those of us working within tri-label WEA were super-happy at the sales results of 1971. Toward the year’s end, Billboard posted company percentages, and WEA (then still referred to as Kinney)came in above every other corp. CBS (Columbia Records) included!

Here’s how Billboard posted record Corporations (with number of charting albums; then percentage of the whole):

Kinney (156) 22.6%

CBS (131) 15.0

RCA (59) 6.4

Capitol (72) 6.2

A&M (36) 5.9

Among our labels and our distribution companies, both national and inter, it was time for “high fives.” We’d become the top, and now felt some feelings even Columbia could no longer. We were not just some little hip island that Columbus had found. No, now we at WEA were a whole big continent. The biggest.

Us vs. Columbia had been part of our unconscious. Their’s too.

We’d heard how Columbia, when pitching a contract to a new artists, talked about those labels in their meager little building (3701 Warner Blvd.), while Columbia had floor upon floor in a modern, zippy building they called “Black Rock” in Manhattan. Lots more staff to do whatever you wanted. How earlier, Columbia’s pres Clive Davis had signed Janis Joplin before we could at Monterey Pop (and how Clive had recently been fired by Columbia for expense account naughties).

Anyway, we didn’t worry about being big-big like other labels, and Columbia was just out there, just a piñata in our business lives.

Seeing that chart in Billboard, I remember rushing with my copy down the hall to Mo’s office, to share Warner joy over this. Mo smiled up at me, thanked me, but didn’t even display a high two over it.

Mo Ostin shared with me what, deeper down, I had never expected to hear from him. He wanted our own labels, the combined Warner-plus-Reprise, to be #1. Sure, he’d share the joy with our brothers at Elektra, Atlantic, and the new Kinney Distribution companies. But deep down, Mo wanted our own label to be #1.

Despite his history at Reprise’s early years, Mo treated those years as by-gones. He wanted to be the new top label. And Mo had a thought how to do just that. It wouldn’t be called Reprise, either.

From his own desk drawer, he pulled out another Billboard chart. This one was for Labels share, not Corporate share. He slid it before me:

Columbia (100) 11.92%

RCA (53) 5.78

Warner Bros. (33) 5.50

Atlantic (30) 5.33

Capitol (57) 5.27

A&M (31) 4.75

Reprise (34) 4.75

I felt Mo staring at that word “Columbia” again. Mo spent hours of his weeks signing acts that would tell him “of course, otherwise, there’s Columbia. They offered us…”

“Now,” Mo told me, “add together the percentages for Warner and Reprise, like they’re one label.” He paused to let me add.

“Ten and a quarter,” I came up with. “Closer to the top.”

I got his feel. Mo was quiet, secure, but, deep down, intent on winning. Winning meant being up on top of this pile, and maybe all piles. “At the Olympics, nobody remembers who came in second in the high jump.”

It was, for Mo, quite simple. Move all the Reprise artists over onto the Warner label. Be a one-label company.

The subject was on the table, and Mo said for us to meet on doing this, and work it out. Work out about Frank Sinatra, who still owned a hunk of Reprise. Frank on Warner Bros.?

Work out other artists, -- Gordon Lightfoot, Maria Muldaur, Neil Young, Randy Newman, Fleetwood Mac, dozens more -- who had affection for the “we’ll do it your way” attitude that Reprise had fostered, mainly through Mo as its manager. And work out hundreds of details, like switching logos on covers and on and on and on.

“Let’s just try it,” said Mo. “We’ve got nothing to lose.”

More Than Just a Name

Mo Ostin and Joe Smith went to work, and put us to work, making us a more attractive, one-name label. Inside marketing, they turned to me (Creative Services) and to sales/promotion (Eddie Rosenblatt) and just said “whatever it takes.”

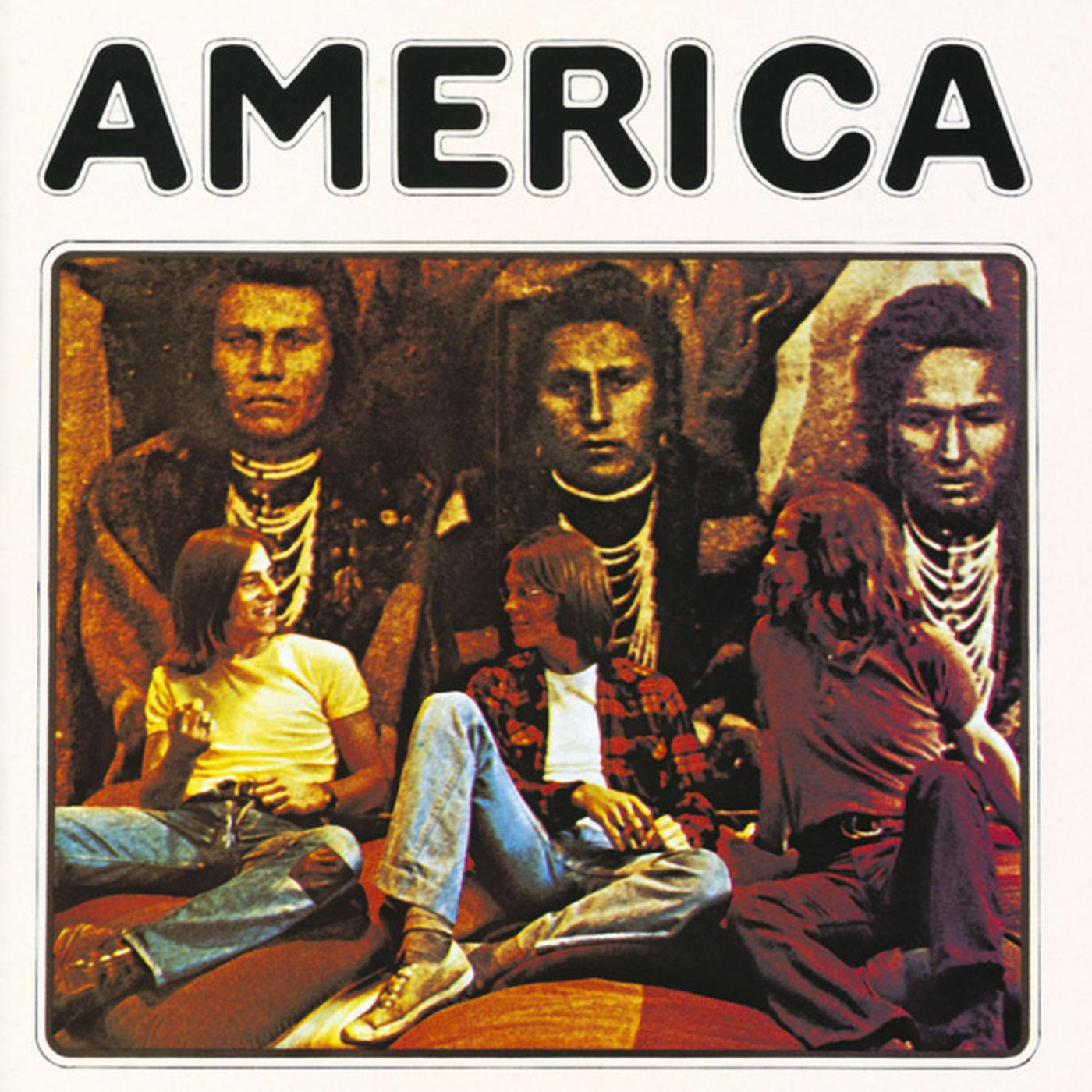

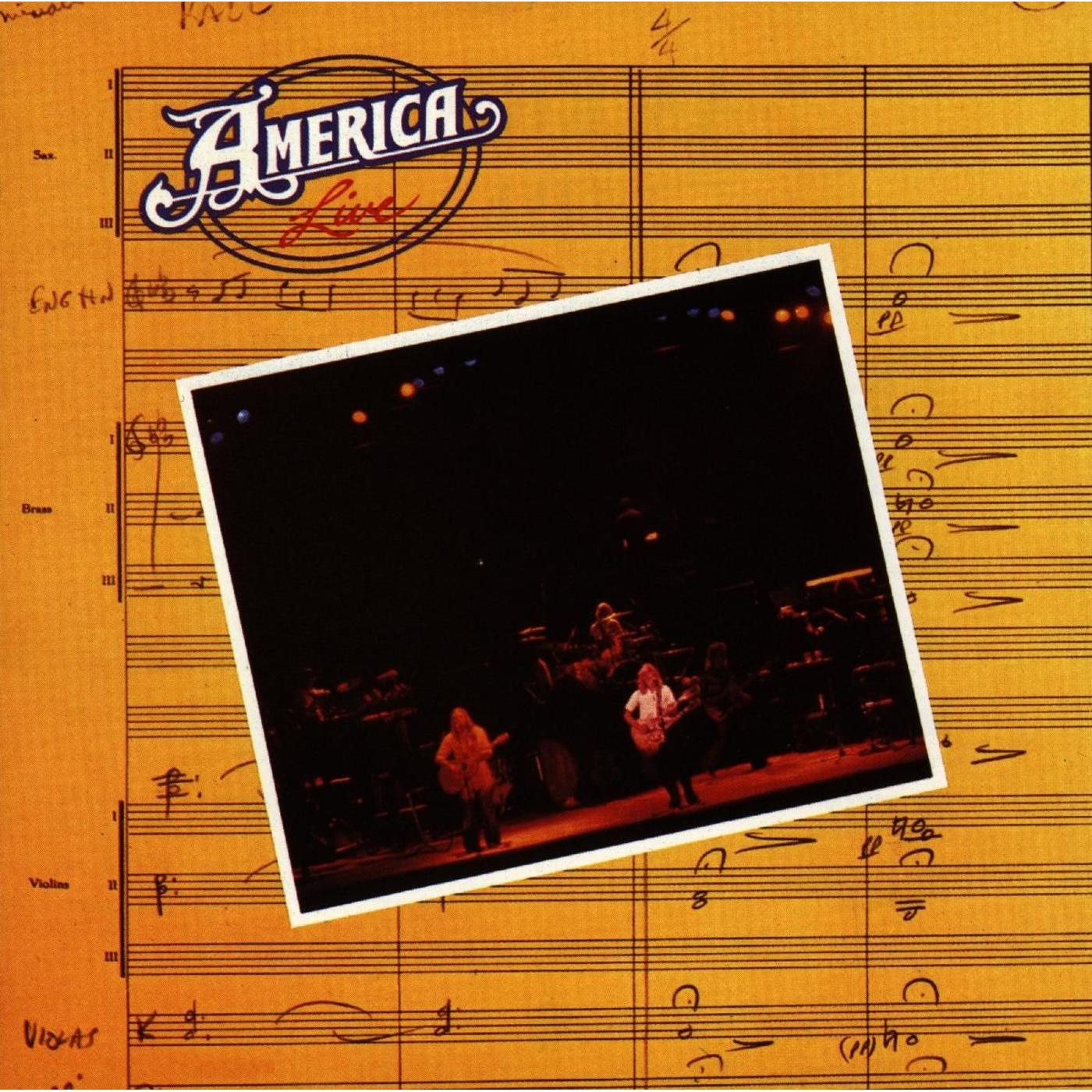

It wasn’t easy for the marketing crews to fix what seemed perfect. In March of 1971, the charts had given the Burbank labels something that had never before happened to one company: we had the #1 and #2 singles on the charts, plus the #1 and #2 albums on the charts; both. Half were Reprise (Neil Young’s Harvest), the other half were America’s America on WBR.

1-2 + 1-2 felt like Warner-Reprise had no need of switching Reprise’s artists over to Warner. But Mo and Joe prevailed. “Whatever it takes,” they repeated.

So we grew it with (and this is just a metaphor) a blank check book. We already felt hip. Now we would also be potent. Our growth plan became simple: “Let’s try it.” “Let’s try it all.”

We set up a potent Artist Relations group under a 6’4” Hollywood get-it-done-publicist named Bob Regehr, and he set up a new department with Carl Scott and Shelley Cooper in a camper truck in our parking lot. Their motto: “Get involved with our artists lives.” Not just with their records.

That meant, when an artist is out on those long, dim tours, they need more than a $6 bouquet delivered to their motel. Ads, contact, local publicity, events they need. (It was Regehr who staged the Coming Out party for Alice Cooper mentioned earlier in “Stay Tuned” under the title “Meeting Alice Cooper.” Click on here to get there).

Switching Reprise artists to Warner was never made “a big deal.” Mostly it was “do us a favor” and most artists did. Switching took us five or six years (say ‘til 1977) until Reprise got slimmed down to two artists: Frank Sinatra and Neil Young. Neil Young has hung on, still on Reprise, even ‘til today, because he always felt Reprise was his home forever.

Most of the others easily slid over to Warner Bros., which felt just the same as Reprise. And for a few, some started their own “distributed by” labels of their own, but those labels work through Warner Bros. Records.

Distributed labels have increased from 1971 until now, when reading reviews of today’s artists comes up with all kinds of label names that average people don’t associate with.

But back in 1971, having one’s own label was somewhat rare. One of the first within WB/R to come up with his “own” was Jesse Colin Young, who named his label “Raccoon Records.”

Jesse’s Youngs on Raccoon Records

Jesse Colin Young’s group name was The Youngbloods, but his Raccoon arrangement with Warner was even simpler. His deal: (1) He could record whatever he liked, doing it in the living room of The Youngbloods’ little home in Marin county; (2) Warner Bros would pay only recording costs. All parties were aware that “a lot of the Raccoon label records would be non-commercial.” But...why not.

This Raccoon deal was all very Peace-and-Love, New Age 1970s, and in the first 18 months of operation, Raccoon came up with six albums, two by The Youngbloods (Rock Festival and Ride the Wind). Other albums by members of the Youngblood’s “All Stars.”

Album after album, Raccoon recorded in its isolated studio on the side of a California mountain. Low environmental impact for the house and its little studio, both built a few hundred yards to where you could climb a bit, peer over the mountain’s summit, and out there was the Pacific Ocean.

Album after album, the music fancies of various Youngbloods – guys named Michael and Jeffrey and Banana, each doing his own thing, his own albums – were recorded. The album masters got mailed down to Warner Records, and left the label’s Burbank execs somewhat puzzled about “what’s this one about?” Critics were left in the dark, as well.

But what Warner Bros. Records (not Reprise) had done was just what Jesse Colin Young had dreamt a label should do. Let him do his things, whether those things sold or didn’t.

But it wasn’t all like Raccoon. On the other hand, Warner Records had some commercial-bent friends with hunger for a label of their own. Alongside Raccoon lived Bearsville.

Grossman was in every respect large, as were his artists: Bob Dylan, Peter, Paul & Mary, The Band, Gordon Lightfoot, Jesse Winchester, Todd Rindgren, and more.

Grossman’s Gang on Bearsville Records

1971 was also the birth year for manager Al “The Great Bear” Grossman, as he set up as “a community” (studio facilities, comfy living quarters for visiting artists, a good restaurant) just west of Woodstock, NY.

Star Bearsville attraction became Todd Rundgren, whose first two albums out on Ampex (Runt and The Ballad of Todd Rundgren) would switch over to Bearsville-via-Warners.

Bearsville’s early chart listings under the Warner umbrella included Foghat’s self-titled album (aka Rock and Roll; with single: “What a Shame”) and Todd Rundren’s Something/Anything? with its singles “Hello It’s Me” and “I Saw the Light.”

And Other Labels

More and more labels would show up under “Warner” distribution, as Reprise slowly faded into the background. Among those labels living in Warner Bros. Records guest houses would become, in 1972,

• Frank Zappa’s Bizarre label;

* The Beach Boys’ Brother label (Pet Sounds);

* Capricorn from Macon, Georgia (The Allman Brothers Band’s Eat a Peach); and

* Chrysalis’ Jethro Tull.

And so slowly, as the years tumbled on, Warner Bros. Records became the label, and Reprise increasingly just felt good to the few.

But would Mo’s Warner label ever out-rank all others on Billboard’s Labels chart?

-- Stay Tuned

* * * * * * * * * *

Extra Extra!

So much of what’s been written about above refers to that March month of 1971 that maybe you’d like to learn what all ten of Warner-Reprise’s TOP TEN ALBUMS were that very week. Here goes:

1. America

2, Neil Young: Harvest

3. Allman Brothers Band: Eat a Peach

4. Malo

5. T. Rex: Electric Warrior

6. Jimi Hendrix: Hendrix in the West

7. “A Clockwork Orange” (Soundtrack)

8. Gordon Lightfoot: Don Quixote