Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Steve Ross Gets Agreeable

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

It’s 1969, and Eliot Hyman – looking to sell off his recent big buy, now known as Warner 7 Arts - had moved Kinney National’s Steve Ross to the top of his list of “Might Buy”-ers. But to Hyman, this move wasn’t an issue of “who.” It was about “how much.”

Selling the studio and records combo had taken some patience, both for the seller and any buyer. W7 wasn’t just a movie studio any longer. And it was not just “owning” record labels. Now the issue behind W7 had become who was running these labels? Any incoming buyer didn’t want to buy, then have all the top “ears” guys just walk away..

Warner-Reprise lived off its signers, most obviously Mo (Ostin) and Joe (Smith). And Hyman had just gotten those two re-signed. Not easily, but done.

Atlantic was going to be a bit dicey. Its hotties – Ahmet, Jerry, and Nesuhi – felt little loyalty to the new, Warner-Atlantic combination. They’d sold their label already. So those three needed to be persuaded to stay, too, because they now owned shares in W7, and those shares meant sharing the whole company’s income now.

Third and finally, there was Frank Sinatra, now owning 20% of the Warner-Reprise combo. He’d have to sign off on a new papa, too.

Month after month, Hyman had trudged through fixing up his W7 to sell. ‘Twasn’t easy.

And for his next target, Steve Ross, buying was definitely his skill.

Steve Ross, a Pro Shopper

Hyman had reached out to New York’s young dealer in companies. Steve Ross was adept at acquiring companies. He was a handsome, tall (I once described his height as “six-feet-plus-one-melon tall”), born-to-hug-ya Steve Ross (born Steven Jay Rechnitz in 1927).

Without overdoing this bio thing, here’s how Ross had gradually moved up in the “companies to buy” business:

1953 – He’d married Carol Rosenthal, whose family owned Riverside Memorial Chapel (funerals arrangements). Steve sold caskets at the “chapel” on West 76th, Manhattan. He learned how to sell caskets. “You learn about people’s needs and feelings at an emotional time for them, a funeral. You service their needs.” He learned to put his hand on buyers’ shoulders. Seven long years there, but Ross worked his way up to managing Riverside. He’d kept talking to the Rosenthal family about “growing” their business.

1960 – Steve Ross merged his in-laws’ funeral home company, Riverside, with Kinney Parking Company of NY (one year after the suicide death of one of Kinney’s “owners,” Mafia boss Abner Zwillman). Ross then takes Kinney Parking public. Never had to sell another casket.

1961 – Ross expanded Kinney Parking into car rentals (funeral limos during the day; theatre limos at night).

1966 - Merged Kinney Parking with National Cleaning Company (for offices). Renames “his” company Kinney National Services, Inc. Ross ran it all.

1967 – He buys National Periodical Publications (DC Comics, starring Wonder Woman, Superman, Batman). Buys MAD magazine.

1967 – He buys Hollywood talent agency Ashley-Famous from its smooth owner, agent Ted Ashley. Ashley-Famous reps record artists ranging from Perry Como to Trini Lopez, Janis Joplin, The Doors, and Iron Butterfly.

1968 – Bought Panavision. Then gets a call from Eliot Hyman, looking for a buyer for Warner-7 Arts, including its “records” labels. Ross conferred with Ted Ashley and others about this. He learned that Warner-7 Arts was clearly a worthwhile buy. Even though Warner Pictures was in a financial slump now.

With Ashley at his side, Ross goes into high gear.

Ross Assembles His Team

His interest in taking over Warner-Seven was his interest in deal making. Steve Ross knew how to get to “yes,” and he knew people. He told Hyman, “Let me see if I can put this together.” Hand on Hyman’s shoulder. Hyman answered gracefully and gratefully.

Ross pulled together the smart people he knew and could work with. He did hours with Ted Ashley, who not only believed that W7 was a good buy (but also that Ted would run it). Ross talked to a NY financial lad, a fast-talking, gum-chewing, hyper-alert Manny Gerard. Manny quickly told Steve, “It’s not a movie company, it’s a record company.” Manny joined in on Steve’s movement.

With other sharp experts, Steve Ross put together what he would need to buy all of it, mostly. The whole ball of wax (including vinyl) – bought with cash, paper, long-term payables – would take $400 million.

Plus: whatever deal Ross could make to buy Sinatra’s 20% of these record labels; that 20% needed to be bought out separately. Ross’ financial negotiator, Alan Cohen, recalled meeting with Sinatra’s lawyer, Mickey Rudin. “Rudin asked me for the world, and he ended up by getting nine-tenths of the world. Sinatra really had veto power.”

Buying Sinatra’s Share

To close the Sinatra deal, Mickey Rudin then met with Steve Ross himself over veal chops in a private room at La Reine restaurant. Mickey’s throat had recently hemorrhaged. He’d been told by his doctor not to talk while it healed. So Rudin wrote his deal notes on paper napkins, and passed them across to Ross. Ross wrote back on his paper napkins. Back and forth, napkins took flight.

By dessert, Sinatra was in. Rudin agreed that Sinatra would sell his remaining 20% of Warner-Reprise for $22.5 million.

For tax reasons, Rudin-with-Sinatra and Ross agreed to sign the papers in New Jersey, in the home of Sinatra’s mother, Dolly. Sinatra had told Ross about his mother’s habit of squirreling away any of her son’s money that she get her hand on.

They met at mom’s in Jersey. As they were closing the deal, Ross held out the paycheck. Dolly grabbed it, but snared only a decoy check for a thousand dollars.

Later, the real money check was privately passed to Sinatra. He folded that check in two, slipped it into his hat’s headband, and was feeling fine as he was chauffeured back into Manhattan.

Ross Meets Ertegun at “21”

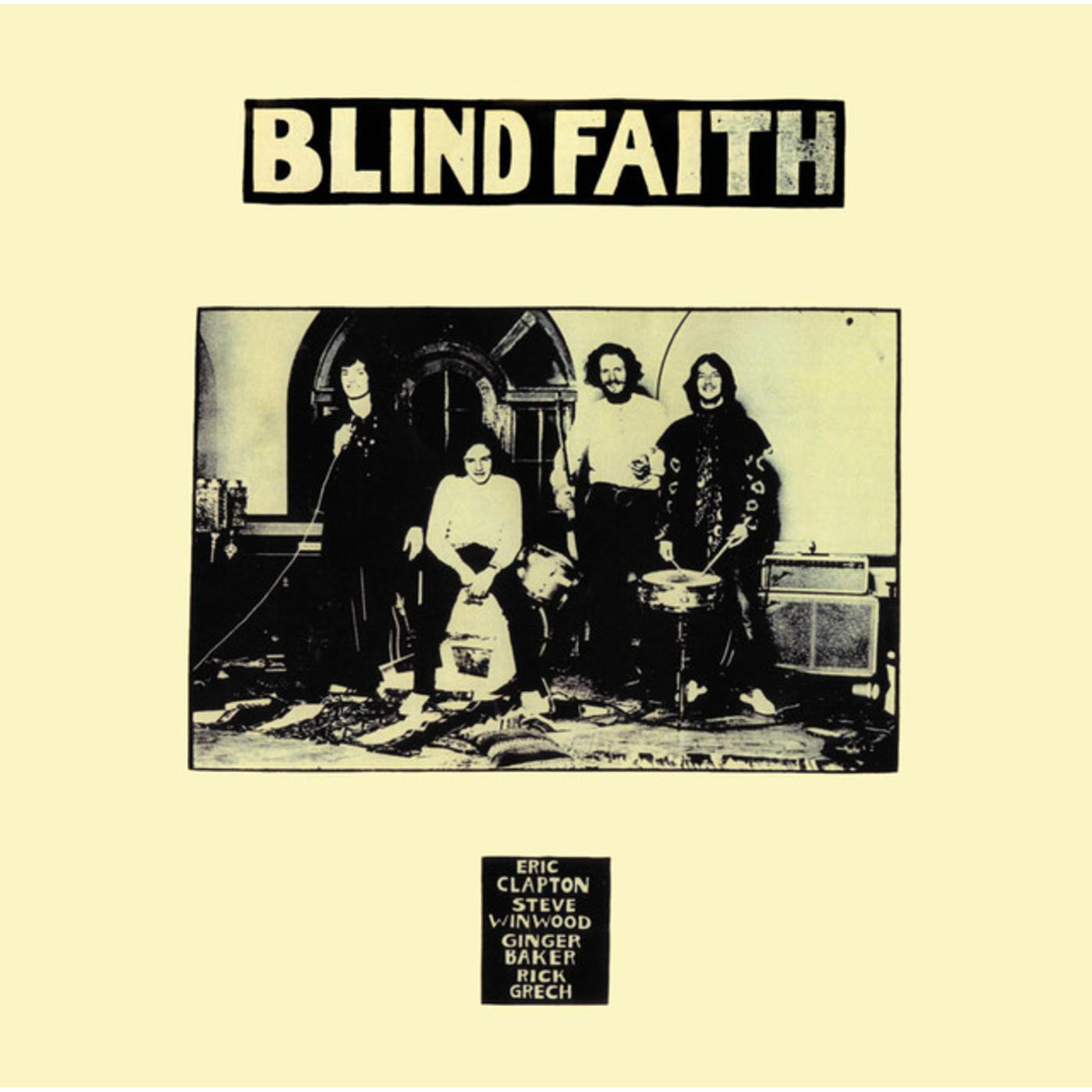

One meeting to go: with Atlantic. Subject: Would Ahmet-Nesuhi-Wexler stick with Atlantic, or walk? At home, Ross overheard one of his sons talk about some Atlantic records, so he tuned in, hearing about some new Atlantic act called Blind Faith, assembled with Stevie Winwood on organ, plus the old Cream, and how even without an album “they’ve sold out Madison Square Garden next week.”

After Ahmet had put off any meeting with this “funeral parlor guy,” he finally got a personal call from Ross. Dinner at “21,” a restaurant with hamburgers sold for the price of used cars. Dinner there was set in a private room. For the two of them. There, Ross opened the talk with “Ahmet, we leave you alone. That’s our pledge.”

Ertegun had heard the same line from Hyman. “Neither of you guys knows diddley about records.”

The dinner and talk at “21” continued for six hours. Their waiter stood by, estimating his tip. Impasse continued, even past midnight.

At 12:45, Ahmet mentioned Atlantic’s newly-signed group, Blind Faith. Ross came back with, “You mean the one with Stevie Winwood on organ, plus the Cream, but you don’t have a record yet, and they’re opening at Madison Square Garden?”

Hearing this, Ahmet’s eyelids rose above half-mast. Ross knows … records? Ten seconds later, Ertegun told Ross that, yes, all right, he would give Kinney a chance. His trio would stay put.

Leaving “21” that morning, their all-evening waiter, glancing at his tip, thought about how maybe he had a down payment on a new home.

1969 – The whole deal finally got shook on. Hyman would sell; Ross would buy. Ross was quoted saying, “If you’re not a risk-taker, get the hell out of the business.”

But About Those Record Labels?

Down actually working at the record labels level, however, in towns like Burbank, all this financial hoopla was “off somewhere,” maybe in the Wall Street Journal, but not in the record business trade mags. Ross, who’s he? Diana’s father?

In Burbank, Mike Maitland was still boss at Warner-Reprise. This guy Ross buying the whole thing, it had nothing to do with the record labels staff, except maybe they’d wait for those painters again to climb up the studio’s water tower to paint over the big W7?

In the meantime, Warner and Reprise and Atlantic and Atco had this year, 1969, to take handle, and that meant plenty of new albums to record and then promote.

Such as:

1969 at Atlantic

Blind Faith on Atco Records, out in August, 1969. The album went #1, and its cover raised lot of attention with its topless teen girl holding what some felt was a flying dildo (she had posed professionally). Blind Faith’s only album.

The Rascals: Time Peace. Greatest hits in white soul becomes a classic. “Good Lovin’,” “Mustang Sally,” and many more.

Aretha Franklin: Soul ’69. She continues her hit string, all produced by Jerry Wexler. Her jazziest hits.

1969 at Warner Bros.

Kenny Rogers and the First Edition. Their debut LP with “Just Dropped In (To See What Condition My Condition Was In)”; “But You Know I Love You”; “Ruby, Don’t Take Your Love to Town.”

Watts 103rd Street Rhythm Band: In the Jungle, Babe with “’Till You Get Enough.”

Sammy Davis, Jr.: “I’ve Gotta Be Me.” Fifteen tracks assembled to show Davis’ deep singing talent.

These and dozens more were being created and marketed by the people working at the labels that Steve Ross just bought. All handled by record label folks who’d never even heard of that Steve Ross guy.

They were about to hear, though. Steve liked to send his companies’ key employees free turkeys for Thanksgiving week. My wife, seeing his “expect a” note, asked me, “How many pounds will our turkey be?” I told her, “I don’t have any idea. Call him and ask.”

She took me seriously. She called Mr. Ross’s office in New York. He answered, put her on hold for a minute, then came back on and said “14 pounds.” She said thank you.

Ross was in my life now, and in the lives of all my record colleagues.

-- Stay Tuned

Whatever Happened To…

Ted Ashley: After W7 got renamed WCI, Ted became the studio’s head until 1981; then vice chairman of WCI corporate until 1988. He fully retired, fell ill of leukemia, and died in New York after a long illness, in 2002.

Eliot Hyman: After selling W7 to Steve Ross’ Kinney National, he retired to become a private investor. He died in 1980.

Mickey Rudin: Continued working as “attorney to the stars” until his death in Beverly Hills in 1999.

Dolly (Natalie) Sinatra: Frank Sinatra’s mother died at age 82 riding a private plane that crashed in Palm Springs, where her son Frank made one of his homes.