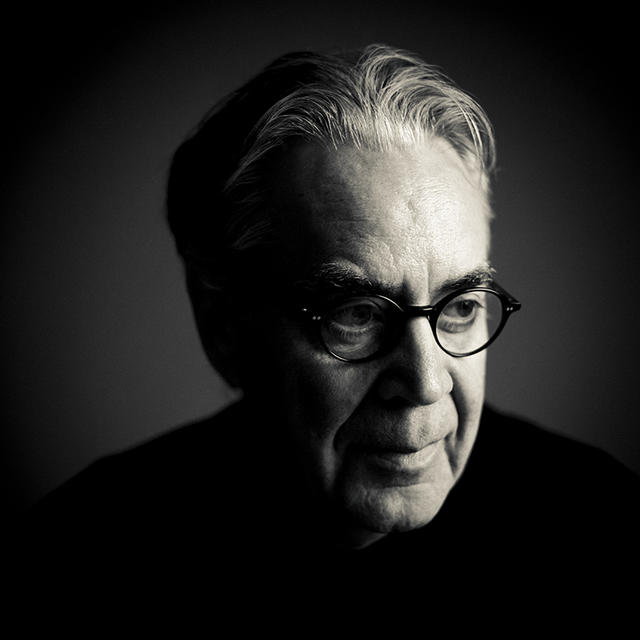

INTERVIEW: Howard Shore (“The Lord of the Rings”)

by Will Harris

Howard Shore started his music career in Canada, playing in the band Lighthouse and working for in both radio and television for the CBC before making his way to New York, and while he wasn’t ready for prime time when he got there, he did secure a pretty sweet gig, serving as musical director for Saturday Night Live for the first five years of the iconic late-night comedy series. Even as he was doing so, however, he was also beginning to write movie scores, starting with the 1978 film, I Miss You – Hugs & Kisses.

Since then, Shore has written scores for more than 80 films, but arguably the most iconic of the bunch have been those that he composed for the Lord of the Rings films. On April 6, Rhino released THE FELLOWSHIP OF THE RING: THE COMPLETE RECORDINGS, available on vinyl for the first time as a 5-LP boxed set and also as a 3-CD / 1 Blu-ray set. In conjunction with this release, Shore spoke with Rhino about how he worked with Peter Jackson in the first place and how much was involved in the process of composing the epic score. (Thankfully, he also kindly indulged us as we asked some questions about other highlights of his career, too.)

Rhino: How did your collaboration with Peter Jackson come about in the first place? Did he approach you directly?

Howard Shore: Yes, I received a phone call directly from Peter, he was in New Zealand – and it was a fascinating project that he described. I journeyed down to New Zealand after the call, the level of filmmaking was amazing and inspiring. I wanted to be a part of it.

Not that it would’ve been necessary to write the score, but had you been a Tolkien fan at all going in?

Yes, very much. I mean, I read The Hobbit and Lord of the Rings in the ‘60s when I was on the road for years traveling, and I loved the books. I didn’t know about the film. I wasn’t aware of it until Peter called that day.

Did you find yourself going back to re-read the book as a source of inspiration?

I did. And I always had the book as a guide. It was always open on my desk, and as I was creating thematic ideas and motifs for the film, I was always re-reading the book. All the time, but especially when I was scoring specific scenes. I would go back to the book and re-read it to gain insight into the story.

You hadn’t really done a whole lot in the fantasy realm. Did you find any challenge in attacking a new territory?

Well, I’d worked in science fiction for quite a few years. You know, with David Cronenberg. But this was a different type of filmmaking. This was a story that’s very complex, it’s considered one of the most complex fantasy worlds ever created. Tolkien doesn’t show you just one world of Elves, he shows you Lothlórien and Rivendell. It’s the same with the worlds of Men. He opens up the universe of Middle-earth to you as a reader, and it’s complex. So the type of storytelling, the way the film was made, it had to have a great sense of logic to it, so that if people hadn’t read the books, people could still understand the storytelling and understand all these various characters that we’re meeting in the film.

Given the massive size and scope of the project, did you have to maintain a writing regiment, or are you someone who tends to have a writing regiment anyway?

I do. I’m pretty disciplined. I write music every day. I worked on this score for almost four years. I was writing and composing every day. I’d do a six-line pencil sketch and then orchestrate in a 30-stave score. And then it goes to the podium, conducting the London Philharmonic, recording, editing the masters, and working with great engineers at Abbey Road in London for everything on the technical side that goes into the final filmmaking process.

Was there ever any point when you were working on it when Peter asked you to tweak something or didn’t particularly like the musical direction in which you were heading?

We worked well together on Lord of the Rings. It was a very good collaboration. Also, I had a good friendship with the other screenwriters, Fran Walsh and Philippa Boyens. So we set out on this journey, and sometimes Peter was holding the light for me, and sometimes I was holding the light for him. We proceeded through Tolkien’s world. We started in the Mines of Moria, a 26-minute piece, that was created for the Cannes Film Festival in May 2001. And when we finished Fellowship of the Ring in the fall of 2001, we went on to The Two Towers and Return of the King. It was a lengthy and very intense few years!

When Peter decided to do The Hobbit and approached you about returning to Middle-earth, did you have any hesitation, knowing the length and intensity in advance this time?

No, we loved The Hobbit. Peter and I actually talked about it when we were making The Two Towers, so it was always kind of in the back of our minds that at some point we would get to visit that Tolkien story, too.

Were there any characters that proved particularly difficult in terms of composing a theme?

No, but in addition to characters, quite a few themes and motifs were used to describe objects. The ring itself has three motifs. Doug Adams wrote a book about the music. He’s an Illinois-based writer. It’s called The Music of the Lord of the Rings Films. He spent nine years working on it. He describes over a hundred themes and motifs in the book.

I wanted to cover a few other things from throughout your career, and since I’m a total music geek, I have to ask about the experience of being a member of Lighthouse.

It was 1969 to 1972. I did a thousand one-nighters in those four years. And it was a great experience, actually. I got to travel the world. I met a lot of other musicians. We opened for [Jimi] Hendrix at the Isle of Wight Festival, we toured with Jefferson Airplane, we opened for the Grateful Dead at the Fillmore… We had the complete experience in the world of rock in those years.

Being that this is for Rhino, I should ask you if you have any specific memories of playing with the Dead.

Well, we opened for them. Then it was the Chambers Brothers who came on after us, and then the Grateful Dead. We opened for them at Fillmore East and West. That was probably 1969 or ’70.

Okay, well, I’ll ask you something from that era that I know you’ll remember: the All-Nurse Band, a classic early-SNL clip.

Oh, right! Yeah, that was a sketch. I was music director for those years, and we did lots of music for sketches. That was one that Michael O’Donoghue wrote. He was a great writer, and it was created for Lily Tomlin.

You’re from Toronto originally, as were several of the cast members, not to mention Paul Shaffer. Was that the connection that brought you into the SNL universe?

Right. I knew Lorne [Michaels] because we both worked at CBC in Toronto for years, and we did shows there. I did CBC Radio and then worked in television. I knew Gilda [Radner] back in that period, also Dan Aykroyd and Paul Shaffer.

You participated in the scores for a couple of SNL films. I was finally able to see Nothing Lasts Forever a few years ago.

Oh, yeah! Tom Schiller! Wonderful.

I know you were also part of Gilda Radner’s live show, but I don’t know the capacity in which you participated.

I was the music director and I co-produced the soundtrack with Jerry Wexler.

SNL was very educational back then when it came to the musical guests. That’s where I was introduced to Tom Waits.

Oh, yeah, Tom Waits! The Band played on SNL, too. And it was one of their last appearances.

Were there any other musical acts who played during that era who stand out to you?

Ornette Coleman. Keith Jarrett. Sun Ra.

How did you and David Cronenberg first hook up as collaborators?

I met David… I knew his films in Toronto from underground film festivals. He’s three years older than I am, so I knew of him when I was 14 and he was a 17-year-old who was already making 8mm and 16mm films. I had done one film before I approached him about working on his film The Brood in 1978, but he took me on, and I did 15 films with him over the years.

Is there a particular favorite of the bunch that stands out to you?

Well, there’s a lot of them. I’m so proud of all 15 films we made. But standouts to me were Dead Ringers, Naked Lunch, The Fly… I liked Cosmopolis and the later works. Maps to the Stars. I love working with David. It was really the backbone of all of my work in film, those 15 films.

Well, I’ll say that I’m personally highly partial to Ed Wood.

Oh, sure! Well, that’s one that gets a lot of play. It gets played in concert quite often. Lydia Kavina plays it regularly. She’s the thereminist who played on the original recording. She’s from Moscow and she studied with the inventor, Leon Theremin. But she plays Ed Wood and performs it all over the world. The last time I saw her was in Paris where she performed the piece last year.

Your score for The Silence of the Lambs is pretty much iconic, particularly the main title.

Oh, yes. That was with Jonathan Demme, who we lost just recently. A great director with whom I did two films: Silence of the Lambs and Philadelphia. But Silence of the Lambs sort of evolved from my work on scores like The Fly, where I was using a symphony orchestra and electronics, and then it led into David Fincher’s movie Se7en. There was a line from The Fly to Silence of the Lambs and then to Se7en.

I think it’d be fair to say that you’ve worked on a few dark-toned projects in the past. Do you ever at a point feel the need to actively lighten it up?

I do on occasion. You mentioned Ed Wood, that’s one. I also did films early in my career like Mrs. Doubtfire, Nadine, and Big.

And I understand you live somewhere that’s particularly conducive to concentration. In a cabin in the forest, is that right?

Right. I’m close to nature, and I draw a lot inspiration from nature. And I think my connection to Tolkien was also through nature. I think that’s how I made that connection to his writing: the love of everything green and good.

You’ve certainly jumped around the genres and the eras in your career. Is there any type of film you haven’t tackled yet that you’d like to try?

I think I’ve covered a lot. You know, I’ve probably worked in every genre of filmmaking.

Have you done a western? I wasn’t sure about that one.

I’ve done films that felt like westerns, but they didn’t necessarily have the trappings. Like, say, A History of Violence. Also, Peter always said that The Two Towers was a western!

One thing I meant to ask earlier but neglected to do so: how did you make the jump from the music you were doing with Lighthouse into doing soundtrack work?

Well, I’d been studying composition since I was quite young, and I learned to write counterpoint and harmony when I was 10, so no matter what I was doing commercially, I was continually writing music on my own all the time. But while I was in Lighthouse for four years, I did CBC radio and television shows and used Lighthouse as the house band for those! So I kind of went from that into documentary films, where I did a lot of nature films and travel films, and then from there into feature films. So that’s the track of how one thing led to another!

For more information, click the buttons below: