Stay Tuned By Stan Cornyn: Arlo’s Restaurant

Every Tuesday and Thursday, former Warner Bros. Records executive and industry insider Stan Cornyn ruminates on the past, present, and future of the music business.

Since 1967, people have wondered about Who Was Alice and Where Was Her Restaurant.

Let’s come out with it right now. There was never a restaurant named Alice or Alice’s. And it was located in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

Alice Brock

Before there was a restaurant, Stockbridge’s young kids – maybe 12 or 14 of them – had hung out (and slept over) at an ex-church in Stockbridge called the Trinity Church.

It had grown old and run down and had been deconsecrated. Empty, the church had been bought for Alice and Ray Brock by Alice’s mother for $2000 for their home. Alice and her husband Ray Brock fixed it up as a live-in for teen-agers a decade younger than Alice, but already homeless because of broken parents or whatever. Or named Arlo. They just moved in. Alice’d make Thanksgiving dinner for them. It felt like family.

“These were kids who felt they didn’t belong in the outside world, and who, because of this, didn’t get along too well with their families.”

Alice would prepare meals in the ex-bell tower, but soon found that this was not her nirvana. In her autobiography (My Life as a Restaurant), she explained, “I was captive in a situation I had very little control over other than the role of cook and nag – being a hippy housewife was not satisfying.”

There was a vacant luncheonette uptown, between Nejaime’s Grocery and Kempton’s Insurance, just off Stockbridge’s Main Street. The Brocks made a down-payment on the luncheonette. It was called The Back Room, and that name was never changed, nor the place ever named Alice’s anything. The kids just referred to it that way.

Arlo, one of those kids, decided he’d write her an ad. His ad copy began with “You can get anything you want at Alice’s Restaurant.” The ad never went on the air, or in the papers.

Arlo Goes Public

Arlo, son of renowned folk song historian and performer Woody Guthrie, had a guitar of his own, and practiced singing with it endlessly. Connected via Woody was life-long folk-music impresario Harold Leventhal. The biggest in that trade, was Harold, working with the cream of folk: Pete Seeger, Brownie McGhee, Sonny Terry, Jack Elliot. And now, 18-year-old Arlo.

Arlo joined the gang at a concert in New York’s Town Hall that was being held as a tribute to Arlo’s health-failing father, Woody, who by now was slowly dying at the Brooklyn State Hospital. Arlo sang two songs, and was hired as an office boy for Harold Leventhal Management, Inc.

In the liner notes for Arlo’s eventual first album for Warner Bros., Leventhal described Arlo’s work/life this way:

“He was a Come-When-He-Wants-To, In-Residence, Part-Time (and Sometimes Part Part-Time) Guitar-Pickin’ Office Boy.

“Of course, whenever there were things to be done such as opening or sealing the mail, pasting clippings, answering the phone, going down for coffee, and the myriad spectrum of responsible office-boy duties, Arlo was not available. He was busy. Practicing the guitar. Writing songs. Singing duets with Pete Seeger whenever Pete walked in the office…”

Arlo wandered for a couple of years. With little money, he’d wandered to London, there getting a cab to take him “where the people are.” Piccadilly Circus, with no room for a bed. Just a-wanderin’.

Back home to Stockbridge, living now at the Church, and after cleaning up after Thanksgiving dinner there, finding the city’s official dump site closed, dumped the carful of waste off a nearby cliff.

Arlo got arrested for that illegal dump by the police chief Wm. J. Obanhein (on the record as “Obie”) who took photos of the illegal dump. Going to court, where the photos couldn’t be seen by the hard-of-seeing judge, Justice Hannon, who just fined Arlo $25 and had to haul the garbage back up the hill. Then, getting to the top of his teens, approached Army induction.

Or as he was to put it:

We took the half a ton of garbage, put it in the back of a red VW Microbus, took shovels and rakes and implements of destruction and headed on toward the city dump.

Well we got there and there was a big sign and a chain across the dump saying, "Closed on Thanksgiving." And we’d never heard of a dump closed on Thanksgiving before, and with tears in our eyes we drove off into the sunset looking for another place to put the garbage.

We didn't find one. Until we came to a side road, and off the side of the side road there was another fifteen foot cliff and at the bottom of the cliff there was another pile of garbage. And we decided that one big pile is better than two little piles, and rather than bring that one up we decided to throw ours down.

That's what we did, and drove back to the church, had a Thanksgiving dinner that couldn't be beat, went to sleep and didn't get up until the next morning, when we got a phone call from officer Obie. He said, "Kid, we found your name on an envelope at the bottom of a half a ton of garbage, and just wanted to know if you had any information about it." And I said, "Yes, sir, Officer Obie, I cannot tell a lie, I put that envelope inder that garbage."

After speaking to Obie for about forty-five minutes on the telephone we finally arrived at the truth of the matter and said that we had to go down and pick up the garbage, and also had to go down and speak to him at the police officer's station. So we got in the red VW microbus with the shovels and rakes and implements of destruction and headed on toward the Police officer's station.

Now friends, there was only one or two things that Obie coulda done at the police station, and the first was he could have given us a medal for being so brave and honest on the telephone, which wasn't very likely, and we didn't expect it, and the other thing was he could have bawled us out and told us never to be seen driving garbage around the vicinity again, which is what we expected, but when we got to the police officer's station there was a third possibility that we hadn't even counted upon, and we was both immediately arrested. Handcuffed. And I said "Obie, I don't think I can pick up the garbage with these handcuffs on." He said, "Shut up, kid. Get in the back of the patrol car."

...and so on.

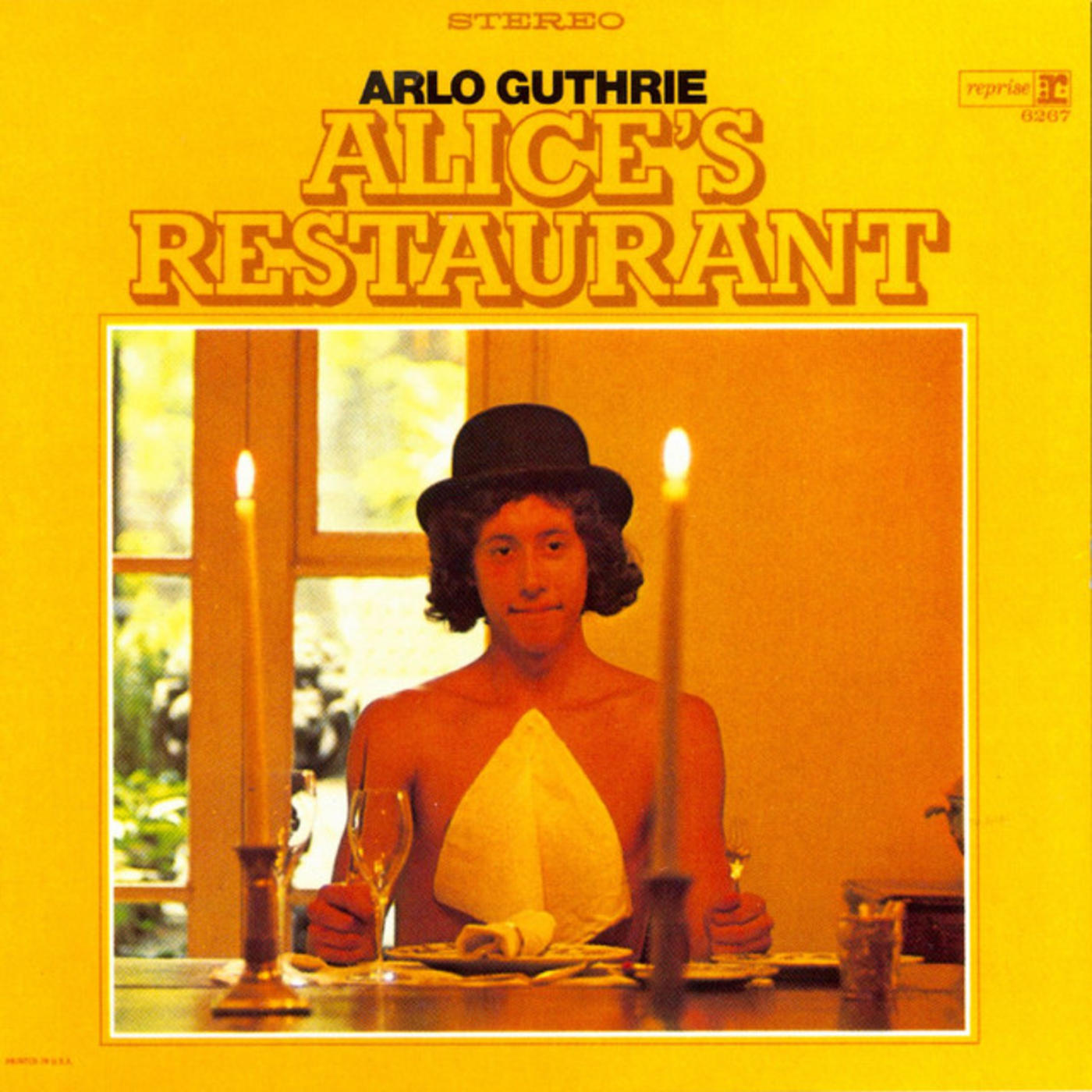

Through all this, Arlo sang and told, with an increasing fan base. Leventhal signed a contract to represent Arlo. When amateur tapes of “Alice’s Restaurant Massacre” got on the air, the word got out, the fans got hotter, and Warner Bros. Records’ New York head, VP George Lee, and WBR’s top decider, Mo Ostin, made a deal for Reprise. Word in Burbank was that Arlo was maybe “the new Dylan.” Probably, because Arlo dressed a bit sloppy and played a brown guitar.

Reprise’s Restaurant

1967. The professionally recorded “Alice’s Restaurant” album was finished by ex-Weaver producer Fred Hellerman. Then, on the eve of its release, father Woody Guthrie, the Dust Bowl balladeer died. It was October 3, 1967. For months, he’d been in near-coma, with no way to communicate with him, but he had been played Arlo’s album.

Three weeks after his death, Reprise placed a trade ad in Billboard for the new album, noting that Arlo would soon be “Breathing New Life into the Guthrie Tradition.”

But Arlo spoke his mind in interviews. In one, he said he was planning to retire his “Alice’s Restaurant Masacree.” Your signature song? Why” “Guthrie answered, “I don’t want to be identified with only one song. There are other songs I want to write and sing, songs I hope will be better.”

Not likely. When he performed at Carnegie Hall, singing songs of his “Urban Dust Bowl,” the house was jammed, standing room only. He sang others of his songs, like his “Ring-Around-a-Rosy Rag” and “Now and Then.”

But it was Side One of his album that got all the attention. Time magazine’s review mentioned none of the shorter songs that made up Side Two. “Its length has kept Alice from wide disk-jockey exposure,” Time continued, “but Arlo’s first Reprise LP is moving steadily up on the charts.”

Rock reviewers put down the album. And at Warner Records, there was frustration that no 45 single could come from the title song of the album. Then, Arlo came to Los Angeles, to play The Troubadour over the New Year’s weekend. On his second night there, he did a twenty-minute long rendition of “The Alice’s Restaurant Multi-Colored Rainbow Roach Affair,” a dope-smoking spy story that floored the audience.

By now, the Reprise album was up to #37 on the Billboard Top 100. Three months later, producer Arthur Penn announced he’d purchased the movie rights to Alice’s Restaurant. (Released in 1969.)

More to Come

As the cameras rolled on the movie, Reprise came out with Arlo’s second album: Arlo. (October, 1968) It had been recorded “live” at The Bitter End the New Year’s of ’68. When Arlo came out, Alice’s Restaurant was still up on the Billboard charts, 59 weeks after its release.

The axis was drawn, reviewers noted. Arlo was searching for his singing style(s), while his record company urged more of his talking routines. Arlo, now a celebrity-style-hippie, wore floppy hats and ruffled fashions.

1969: Album Three brought in a new producing team (co-produced by Lenny Waronker and Van Dyke Parks) to make Running Down the Road. The LP’s dope-smuggling anthem, “Coming Into Los Angeles,” was named “the best tune he’s written.”

1972: Album Four became Arlo’s second-best-ever album in sales: Hobo’s Lullaby, and its single “City of New Orleans.” It stayed charted for 32 weeks. And of all things, it became #1 on the Austrian Top 40 chart, which caused WBR to place an ad wishing “a hearty Gluckwunsche to Mr. G.”

More Reprise albums would follow, but the recording world had gone past Alice’s by now. No longer a world, it was now “the record business,” and Arlo didn’t feel about life that way.

He joined a mass of talented recorders who are remembered for one great song.

In 1982, the town of Pittsfield in Massachusetts asked Arlo to be the Grand Marshall of its Fourth of July parade. The town’s officials told Arlo he’d received this honor because his songs were most grateful to “Mom, apple pie, and America.” To which Arlo replied, with a smile, “I liked that.”

- Stay Tuned